An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov

website belongs to an official government organization in the

United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock

(

) or

https://

means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.

Growth of Health IT-Enabled Patient Engagement Capabilities Among U.S. Hospitals: 2021-2024

No. 79 | September 2025

Electronic health records (EHR) enable patient engagement with their health information, fostering better patient care, improved outcomes, increased transparency, and a more efficient healthcare system1,2. Federal policy incentivizes hospitals to adopt capabilities that enable patient access to their electronic health information3, which in turn allows patients to manage their health using smartphone health applications (apps) of their choice4. Federal policy, along with patient demand for virtual care options following the COVID-19 pandemic, have driven growth in patient engagement capabilities in hospital settings. Still, many hospitals continue to lack capabilities enabling patients’ access to health information5,6. This brief examines trends in hospitals’ adoption of nine key patient engagement capabilities in both inpatient and outpatient settings, including the ability of patients to: view, download, transmit, and import data from other organizations into their patient portal; view clinical notes; and access information through apps. It also explores variation by hospital and health IT characteristics. These findings can help inform policymakers’, health systems’, and health IT developers’ efforts to promote access to digital health tools.

Highlights

- In 2024, most hospitals had adopted foundational patient engagement capabilities that enable patients to electronically view, download, and transmit their health information and securely message their providers.

- From 2021 to 2024, hospital adoption of patient engagement capabilities increased.

- In 2024, 8 in 10 hospitals had all foundational capabilities, 2 in 3 had all emerging capabilities enabling patients to view clinical notes and access information via apps, and fewer than half had all advanced capabilities (record import and patient-generated data submission) in any setting.

- Hospitals’ adoption of patient access capabilities increased significantly between 2021 and2024, with overarchingly stable adoption rates through 2024 in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

- Lower-resourced (e.g., small, rural, Critical Access, or independent) hospitals lagged in their adoption of app-based and FHIR-enabled patient engagement capabilities.

In 2024, nearly all hospitals enabled patients to electronically view and download health information.

Findings

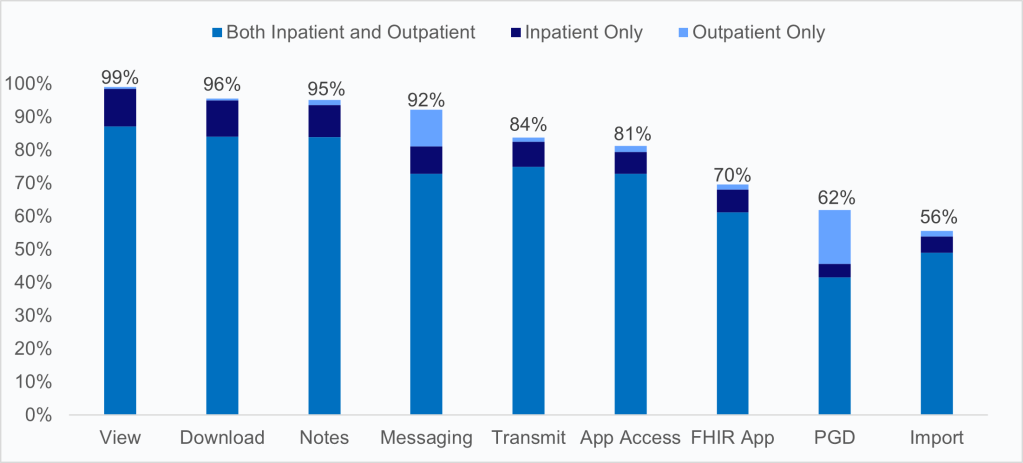

- In 2024, most hospitals had adopted patient engagement capabilities that enable patients to electronically view (99%) (e.g., test results), download (96%), and transmit their health information to a third party (84%).

- Hospitals also widely adopted capabilities that enable patients to electronically view their clinical notes (95%) and securely message with their provider (92%).

- Eighty-one percent of hospitals enabled patient access using apps configured to meet application programming interface (API) specifications in their EHR (“app access”) and 70% enabled access using apps configured to meet HL7® Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource® (FHIR®)specifications (“FHIR app”).

- A lower share of hospitals had more advanced capabilities that enable patients to import their records from other organizations into the patient portal (56%) or submit their own patient-generated data (PGD) (62%), such as blood glucose or weight, through apps.

- Patient engagement capabilities were most commonly enabled in both inpatient and outpatient settings. However, secure messaging (11%) and PGD (16%) had a higher proportion of hospitals where these functionalities were available only in outpatient settings.

Figure 1: Non-federal acute care hospitals’ adoption of nine patient engagement capabilities across settings, 2024

Notes: Figure labels represent short-hand descriptions of responses to a question asking whether the hospital provides specific patient engagement capabilities to their patients. A full description of patient engagement capabilities is available in the Definitions section. Hospitals that completed the IT Supplement but did not answer any patient engagement questions are excluded from estimates.

Hospitals steadily increased patient engagement capabilities between 2021 and 2024, though adoption of emerging and more advanced capabilities lagged behind foundational ones.

Findings

- Foundational patient engagement capabilities incentivized by the CMS Promoting Interoperability Program authorized by the HITECH Act (i.e., view, download, transmit, and secure messaging) showed the highest adoption rates across all years, with 80% of hospitals adopting all four capabilities by 2024 after significant growth from 72% in 2021.

- The share of hospitals that had adopted capabilities that align with the Cures Act and information blocking polices (i.e., access to clinical notes and any type of app access) had an overall increase from 65% in 2021 to 85% in 2024.

- While adoption of more advanced patient engagement capabilities not yet supported by federal policies (i.e., import, submitting PGD) were lower, the share of hospitals that adopted both capabilities grew consistently from 37% in 2021 to 45% in 2024.

Figure 2: Non-federal acute care hospitals’ adoption of foundational, emerging, and advanced engagement capabilities in any setting, 2021-2024

In the last 4 years, hospitals expanded app-based tools for patient access, with strong early growth followed by generally stable adoption rates since 2022.

Findings

- Between 2021 and 2024, hospitals’ adoption of app-based tools for patient access was higher in inpatient settings compared to outpatient settings.

- In the inpatient setting, hospitals’ use of APIs to enable patient access via apps grew from 2021 to2023 (from 68% to 83%) but had a modest decline (from 83% to 80%) from 2023 to 2024.

- In the outpatient setting, hospitals’ use of FHIR-based APIs to enable patient access via apps grew from 62% in 2021 to 74% in 2022, with rates remaining overarchingly steady between 2022to 2024.

- Adoption of FHIR-based apps allowing patients to access their health information increased across both settings through 2022 and has remained relatively stable. In inpatient settings, rates grew from 56% in 2021 to 69% in 2024. In outpatient settings, adoption increased from 49% in2021 to 64% in 2024.

Lower-resourced hospitals lagged in their adoption of emerging capabilities that enable patient access using apps.

Findings

- Hospitals’ adoption of capabilities that enable patients to access their information via apps varied by hospital characteristics, with lower-resourced hospitals lagging in rates of adoption of capabilities that enable app and FHIR-based app access.

- Rates of adoption of app access capabilities were higher among hospitals using the market leading EHR developer compared to hospitals using other EHR developers (92% vs. 70% for app access, 83% vs. 56% FHIR app access).

Table 1: Non-federal acute care hospitals’ adoption of capabilities that enable patients to access their health information using apps in any setting, by hospital and health IT characteristics, 2024

| App Access | FHIR App Access | |

|---|---|---|

| All hospitals | 81% | 70% |

| Hospital size | ||

| Small | 76%* | 66%* |

| Medium | 85%* | 71%* |

| Large (ref) | 94% | 84% |

| Teaching status | ||

| Teaching | 87%* | 75%* |

| Non-teaching | 76% | 65% |

| Location | ||

| Urban | 86%* | 72%* |

| Rural | 74% | 66% |

| Critical Access Hospital (CAH) | ||

| CAH | 72%* | 64%* |

| Non-CAH | 85% | 72% |

| System affiliation | ||

| System-affiliated | 86%* | 76%* |

| Independent | 71% | 56% |

| Ownership | ||

| For-profit | 81%* | 26%* |

| Non-profit (ref) | 85% | 83% |

| Government | 70%* | 58%* |

| EHR Developer | ||

| Market Leader | 92%* | 83%* |

| Other | 70% | 56% |

Notes: access = capability to enable patients to access their health information using apps configured to meet the API specifications in the hospital’s EHR. FHIR app = capability to enable patients to access their health information using apps configured to meet FHIR specifications. A full description of patient engagement capabilities is available in the Definitions section. *Indicates statistically significant difference at the 5% level (P<.05). Estimates include all hospitals with inpatient and/or outpatient settings. Hospitals that completed the IT Supplement but did not answer any patient engagement questions are excluded from estimates.

Summary

Post-COVID, there has been both an increase in patient access to electronic health information and in demand for methods of viewing and managing health information electronically 7,8,9,10. These shifts have created a “new normal” in healthcare delivery, where patients now expect near instant access to their electronic health information11. We found widespread adoption of digital patient engagement capabilities among U.S. hospitals that enable patients to view, download, and transmit data; import records from other organizations into a patient portal; view clinical notes; access information via apps; submit patient-generated data; and securely message their providers.

In 2024, most hospitals had adopted foundational capabilities that enable patients to electronically view (99%), download (96%), and transmit (84%) their health information from their online medical record in at least one setting, as well as securely message with their providers (92%). These foundational capabilities have long been supported by certification criteria from the ONC Health IT Certification Program and other federal initiatives such as the Promoting Interoperability Program 3,12. As the result of updates to the Certification Program and Promoting Interoperability Program surrounding the 21st Century Cures Act and its relevant health IT provisions4, many hospitals allow patients to view clinical notes electronically (95%), access their health information using apps (81%), and access their information using apps configured to meet the FHIR specifications (70%). However, certain advanced capabilities, not currently supported through these federal programs, are not yet widely adopted among hospitals. Currently, a lower share of hospitals enable patients to import their records (56%) or submit patient-generated data via apps (62%), potentially due to the challenges in workflow integration and technical constraints, lack of demand for those functions, and absence of policy or program incentives to do so.

Hospitals’ overall adoption of patient engagement capabilities has increased over time. This signals broader availability of digital tools that enable patients to manage their health information across foundational, emerging, and advanced capabilities. Adoption of these functionalities had significant growth between 2021 and 2022, followed by slower but continued growth through 2024. During this period, the percentage of hospitals with all four foundational capabilities (view, download, transmit, and message) increased 11% (from 72% to 80%), emerging capabilities (notes and any type of app access) increased 31% (from 65% to 85%), and both advanced capabilities (import, PGD) increased 22% (from 37% to 45%). The upward trend in advanced capabilities highlights hospitals’ growing readiness to support patient access and engagement, even in the absence of specific policies or other federal nudges.

The Cures Act Final Rule aimed to enhance patient access by ensuring that patients can electronically access their health information at no cost, using an app of their choice4. Over the past four years, there has been significant progress in hospital use of APIs (16% growth) and standards-based APIs (23% growth) that enable patient access via apps across care settings. Adoption trends for these patient access capabilities, however, varied by hospital setting, with a higher rate of app-based patient access in inpatient settings compared to outpatient settings. In addition, adoption trends for these patient access capabilities were not uniform across hospital types. Smaller, rural, non-teaching, critical access and independent hospitals were less likely to provide these capabilities. Also, hospitals using the market-leading EHR developer were significantly more likely to have the capabilities of both app access (92%) and FHIR-enabled app access (83%) compared to those using other developers (70% and 56%, respectively). Differences in adoption by hospital characteristics underscore the role of vendor capabilities and organizational resources in shaping adoption of these important patient engagement capabilities. These differences may help explain the flattening in trends, suggesting that barriers, including technical, financial, and operational, may limit progress.

Despite the benefits of these technologies to enhancing patient access, there is the potential for some of these capabilities to create unintended consequences for clinicians. Specifically, the volume of inbox messages represents a growing source of unmeasured care delivery. Therefore, workflow optimization and support are critical to help promote seamless access to electronic health information while avoiding undue burden for clinicians13. Further, findings indicate that U.S. hospitals have made major headway in foundational and emerging patient engagement capabilities, but gaps remain among lower-resourced hospitals. It is important to support advancements in patient engagement capabilities while ensuring broader adoption of foundational digital health tools to advance nationwide engagement and achieve the goal of a patient-centric healthcare system14.

Definitions

Critical Access Hospital: Hospitals less than 25 beds and at least 35 miles away from another general or Critical Access hospital.

Large hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals with bed sizes of 400 or more.

Medium hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals with bed sizes of 100 to 399 beds.

Non-federal acute care hospital: Includes acute care general medical and surgical, children’s, and cancer hospitals owned by private/non-for-profit, investor-owned/for-profit, or state/local government and located within the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

View: Patients treated in a hospital are able to view their health/medical information online.

Download: Patients treated in a hospital are able to download information from their health/medical record.

Transmit: Patients treated in a hospital are able to electronically transmit (send) transitions of care/referral summaries to a third party.

View, Download, and Transmit: Patients treated in a hospital are able to view their health/medical record online, download information from their health/medical record, and transmit (send) transitions of care/referral summaries to a third party.

Import: Patients treated in a hospital are able to import their medical records from other organizations into their portal.

Notes: Patients treated in a hospital are able to view their clinical notes (e.g., visit notes including consultation, progress, history, and physical) in their portal.

App Access: Patients treated in a hospital are able to access their health/medical information using applications (apps) configured to meet the application programming interfaces (API) specifications in their HER.

FHIR-based App Access: Patients treated in a hospital are able to access their health/medical information using applications (apps) configured to meet Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR) specifications.

Patient Generated Data: Patients treated in a hospital are able to submit data they generate (e.g., blood glucose, weight).

Messaging: Patients treated in a hospital are able to send/receive secure messages with providers.

Inpatient Setting: Sites where patients are formally admitted to the hospital and stay overnight or longer for treatment.

Outpatient Setting: Sites within a hospital’s campus or care facility where patients receive treatment without being admitted overnight.

Small hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals with bed sizes of 100 or less.

System affiliated hospital: A system is defined as either a multi-hospital or a diversified single hospital system. A multi-hospital system is two or more hospitals owned, leased, sponsored, or contract managed by a central organization. Single, freestanding hospitals may be categorized as a system by bringing into membership three or more, and at least 25 percent, of their owned or leased non-hospital pre-acute or post-acute health care organizations.

Data Sources and Methods

Data are from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Information Technology (IT) Supplement to the AHA Annual Survey from 2021-2024. Since 2008, ASTP has partnered with the AHA to measure the adoption and use of health IT in U.S. hospitals. ASTP funded the AHA IT Supplement to track hospital adoption and use of EHRs and the exchange of clinical data.

The chief executive officer of each U.S. hospital was invited to participate in the survey regardless of AHA membership status. The person most knowledgeable about the hospital’s health IT (typically the chief information officer) was requested to provide the information via a mail survey or a secure online site. Non respondents received follow-up mailings and phone calls to encourage response.

The 2024 survey was fielded from April to September 2024. The response rate for non-federal acute care hospitals (N = 2,253) was 51 percent. A logistic regression model was used to predict the propensity of survey response as a function of hospital characteristics, including size, ownership, teaching status, system membership, and availability of a cardiac intensive care unit, urban status, and region. Hospital-level weights were derived by the inverse of the predicted propensity.

Data Availability

The complete 2024 American Hospital Association IT Supplement data is available from the AHA:

https://www.ahadata.com/aha-healthcare-it-database. If you have questions or would like to learn more about the data source or these findings, you may contact ASTP_Data@hhs.gov.

References

- Upadhyay S, Bhandari N. Patient Engagement Capabilities’ Influence on Quality Outcomes: The Road via EHR Presence. Journal of Healthcare Management. 2024 Mar 1;69(2):118-31 Available from;

- Asagbra OE, Burke D, Liang H. The association between patient engagement HIT functionalities and quality of care: Does more mean better? International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2019 Oct;130:103893

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Promoting Interoperability Programs 2024. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; [updated 2024; cited 2025 May 29]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/regulations-guidance/promoting-interoperability-programs

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, information blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program (85 FR 25642). Washington (DC): Federal Register; 2020 May 1 [cited 2025 May 29]; Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/05/01/2020-07419/21st-century-cures-act-interoperability-information-blocking-and-the-onc-health-it-certification

- Henry J., Barker, W., & Kachay, L. Electronic Capabilities for Patient Engagement among U.S. Non- Federal Acute Care Hospitals: 2013-2017. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy. Data Brief: 45. April 2019.

- Johnson C. & Barker W. Hospital Capabilities to Enable Patient Electronic Access to Health Information, 2019. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy. Data Brief: 55. June 2021.

- Asagbra OE, Zengul FD, Burke D. Patient engagement functionalities in U.S. hospitals. Journal of Healthcare Management. 2019 Nov-Dec;64(6):381–96. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/jhm-d-18-00095

- Upadhyay S, Opoku-Agyeman W, Choi S, Cochran RA. Do patient engagement IT functionalities influence patient safety outcomes? A study of US hospitals. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2022 Sep-Oct;28(5):505–12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000001562

- Richwine C. Progress and persistent disparities in patient access to electronic health information. JAMA Health Forum. 2023 Nov;4(11):e233883. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.3883

- Lee P, Abernethy A, Shaywitz D, Gundlapalli AV, Weinstein J, Doraiswamy PM, Schulman K, Madhavan S. Digital health COVID-19 impact assessment: lessons learned and compelling needs. NAM Perspectives. 2022 Jan [2022]:10.31478/202201c. Available from: https://nam.edu/perspectives/digital-health-covid-19-impact-assessment-lessons-learned-and-compelling-needs/

- Ndayishimiye C, Lopes H, Middleton J. A systematic scoping review of digital health technologies during COVID-19: a new normal in primary health care delivery. Health Technology. 2023;13(2):273-84. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-023-00725-7

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. About the ONC Health IT Certification Program 2025. Washington (DC): Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; [updated 2025; cited 2025 May 29]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/topic/certification-ehrs/about-onc-health-it-certification-program

- Budd J. Burnout related to electronic health record use in primary care. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2023 Jan–Dec;14:21501319231166921. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319231166921

- Barker W, Chang W, Everson J, Gabriel M, Patel V, Richwine C, Strawley C. The evolution of health information technology for enhanced patient-centric care in the United States: data-driven descriptive study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2024;26:e59791. Available from: https://www.jmir.org/2024/1/e59791

Acknowledgements

The authors are with the Office of Standards, Certification, and Analysis, within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy/National Coordinator for Health IT (ASTP/ONC). The data brief was drafted under the direction of Mera Choi, Director of the Technical Strategy and Analysis Division, Vaishali Patel, Deputy Director of the Technical Strategy and Analysis Division, and Wesley Barker, Chief of the Data Analysis Branch.

Suggested Citation

Gabriel MH, Richwine C, Owusu-Mensah P, Strawley C. Health IT-Enabled Patient Engagement Capabilities Among U.S. Hospitals: 2024. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy. Data Brief: 79. August 2025.

Appendix

Appendix Table A1: Non-federal acute care hospitals’ adoption of patient engagement capabilities, 2021-2024: Any Setting

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| View | 98% | 99% | 99% | 99% |

| Download | 94% | 96%* | 96% | 96% |

| Import | 49% | 52%* | 56%* | 56% |

| Transmit | 78% | 83%* | 84% | 84% |

| Notes | 86% | 93%* | 94% | 95% |

| App access | 70% | 82%* | 84% | 81%* |

| FHIR app | 57% | 68%* | 70% | 70% |

| PGD | 54% | 58%* | 60% | 62% |

| Messaging | 89% | 92%* | 92% | 92% |

Notes: Figure labels represent short-hand descriptions of responses to a question asking whether the hospital provides specific patient engagement capabilities to their patients. A full description of patient engagement capabilities is available in the Definitions section. *Indicates statistically significant difference from the prior year at the 5% level (P<.05). Estimates include all hospitals with inpatient and/or outpatient settings. Hospitals that completed the IT Supplement but did not answer any patient engagement questions are excluded from estimates.