An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov

website belongs to an official government organization in the

United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock

(

) or

https://

means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.

Interoperability and Methods of Exchange among Hospitals in 2021

No. 64 | January 2023

- Interoperability and Methods of Exchange among Hospitals in 2021 [PDF – 382.79 KB]

- Data Brief 64 Figure 1 [PNG – 35.12 KB]

- Data Brief 64 Figure 2 [PNG – 17.34 KB]

- Data Brief 64 Figure 3 [PNG – 32.12 KB]

- Data Brief 64 Figure 4 [PNG – 23.06 KB]

- Data Brief 64 Figure 5 [PNG – 33.04 KB]

- Data Brief 64 Figure 6 [PNG – 66.83 KB]

- Data Brief 64 Appendix Figure 7 [PNG – 125.31 KB]

- Data Brief 64 Figure 1 [CSV – 305 bytes]

Interoperable exchange of health information or “interoperability” is critical for delivering appropriate care, reducing health care costs, and making health care more efficient (1-3). ONC is executing on a number of health IT provisions from the 21st Century Cures Act, such as the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) and Information Blocking provision that seek to advance interoperability (4-5). As these provisions are implemented, it is important to monitor interoperable information exchange to evaluate present policies and undertake future actions to advance interoperability. This data brief presents the state of interoperability among hospitals, as of 2021. We present trends on information exchange and the availability and use of information at the point of care, while also highlighting key barriers to interoperability. Additionally, we highlight the methods hospitals used to exchange health information and their participation in national networks and health information exchanges (HIEs).

Highlights

- In 2021, more than 6 in 10 hospitals engaged in key aspects of electronically sharing health information (send, receive, query) and integrating of summary of care records into EHRs, a 51 percent increase since 2017.

- Availability and usage of electronic health information received from outside sources at the point of care significantly increased over the last four years, reaching 62 and 71 percent, respectively, in 2021.

- Health Information Service Providers (HISPs) and HIEs were the most common methods used for electronic exchange among hospitals.

- About three-quarters of hospitals participate in health information exchange organizations (HIEs) and about 35 percent participate in both HIEs and national networks.

- In 2021, 39 percent of hospitals reported participating in more than one of four measured national networks.

- Nearly 90 percent of hospitals upgraded their EHRs to 2015 Edition through 2021 and 74 percent of hospitals adopted bulk data export technology.

Hospitals’ engagement in three domains of interoperability (receive, find, and integrate) significantly increased since 2017.

Findings

- About 80 percent of hospitals electronically queried or found any patient health information in 2021.

- Since 2017, rates of integrating summary of care records demonstrated the largest improvements (21 percentage points) followed by finding information (19 percentage points).

- The percent of hospitals that engaged in all aspects of exchange (send, receive, query) and integrating of summary of care records into EHRs increased by 51 percent from 2017-2021.

Figure 1: Percent of U.S. non-federal acute care hospitals engaging in electronically sending, receiving and integrating summary of care records and searching/querying any health information 2017-2021.

Notes: See Definitions for detailed definitions of interoperability domains. Study population are non-federal acute care hospitals. See Data Sources and Methods for more information. *Significantly different from 2017 (p<0.05).

Small and rural hospitals made significant gains in having information electronically available at the point of care, reaching 50 percent in 2021.

Findings

- Overall, the percent of hospitals with information available at the point of care increased by 22% between 2017 and 2021, while rural and small hospitals’ rates of having information available increased by over 25%.

- Usage of information received electronically from outside sources increased at twice the rate for rural and small hospitals versus their counterparts (40% vs. 20%) between 2017 and 2021.

- Rural and small hospitals lagged their counterparts in engagement in four domains of interoperability in 2017 and 2021.

Table 1: Percent of hospitals having availability and use of patient health information electronically received from outside sources by hospital type, 2017 vs. 2021.

| Hospital Type | 2017 (%) | 2021 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Information Available from Outside Sources | ||

| All Hospitals | 51 | 62* |

| Suburban/Urban | 61 | 71* |

| Rural | 38 | 48* |

| Medium/Large | 61 | 72* |

| Small (under 100 beds) | 41 | 52* |

| Use of Electronic Health Information Received from Outside Sources | ||

| All Hospitals | 55 | 71* |

| Suburban/Urban | 64 | 77* |

| Rural | 42 | 61* |

| Medium/Large | 64 | 78* |

| Small (under 100 beds) | 46 | 65* |

| Engagement in all Four Domains of Interoperability (see Figure 1) | ||

| All Hospitals | 41 | 62* |

| Suburban/Urban | 51 | 72* |

| Rural | 27 | 48* |

| Medium/Large | 50 | 74* |

| Small (under 100 beds) | 32 | 51* |

Notes: *Significantly different from 2017 (p<0.05).

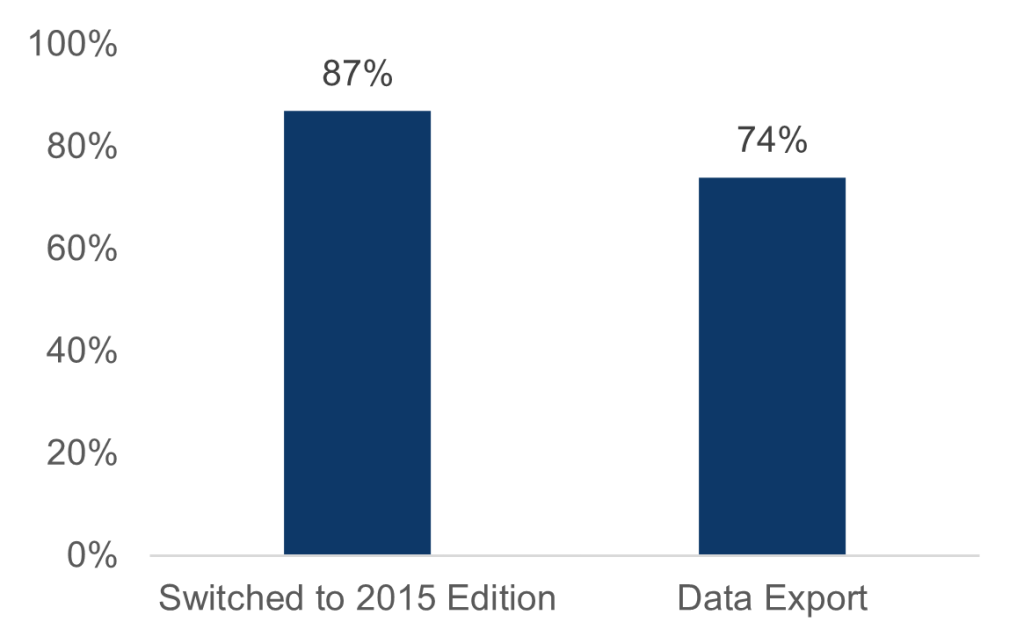

As of 2021, almost nine out of ten hospitals had upgraded their EHRs to the most recent certified EHR technology (2015 Edition).

Findings

- Almost three-quarters of hospitals incorporated bulk data export technology into their EHRs as of 2021. The bulk data export technology enables a hospital to export patient data for all or some of its patients simultaneously.

- Among hospitals that adopted bulk data export technology, analytics and reporting was the most common use of bulk data export technology (84 percent) followed by population health management (47 percent).

- Among hospitals that adopted bulk data export technology, only 12 percent of hospitals had not used bulk data export technology.

Figure 2. Percent of hospitals that upgraded EHRs to 2015 Edition and adopted bulk data export technology, 2021.

Table 2. Percent of hospitals that applied data export technology for specific uses among those that adopted bulk data export technology, 2021.

| Uses of bulk data export capability | % |

|---|---|

| Analytics and reporting | 84 |

| Population health management | 47 |

| Switching EHR systems | 12 |

| Have not used the capability yet | 12 |

Note: Sample consists of hospitals that reported having bulk data export capability. Information Technology Supplement, 2021. Sample consists of hospitals that reported having bulk data export capability.

The use of HISPs and HIEs remain the most common methods hospitals used for electronically sending and receiving summary of care records in 2021.

Findings

- About half of hospitals used interface connections that did not involve third-parties or networks to electronically send patient health information.

- Access to other organizations’ EHR system using login credentials and interface connection between EHR systems were the least common methods used by hospitals for receiving summary of care records.

Table 3: Percent of hospitals that often or sometimes send or receive summary of care records with sources outside their hospital system by method, 2021.

| Method | Send (%) | Receive (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Method Not Using Third-Party or Network | ||

| Provider portal that enables viewing of another organizations’ EHR system | 55% | 34% |

| Interface connection between EHR systems (e.g. HL7 interface) | 48% | 28% |

| Access to other organizations’ EHR system using login credentials | 53% | 26% |

| Electronic Method Using a Third-Party or Network | ||

| HISPs that enable messaging via Direct protocol | 68% | 58% |

| State, regional, or local HIE | 65% | 56% |

| EHR vendor-based network that enables exchange between users of a single EHR vendor | 44% | 43% |

| National networks that enable exchange across different EHR vendors (e.g. Carequality) | 47% | 45% |

| Non-Electronic Method | ||

| Mail or fax | 69% | 78% |

| eFax using EHR | 67% | 62% |

Notes: National networks exclude EHR vendor-based networks.

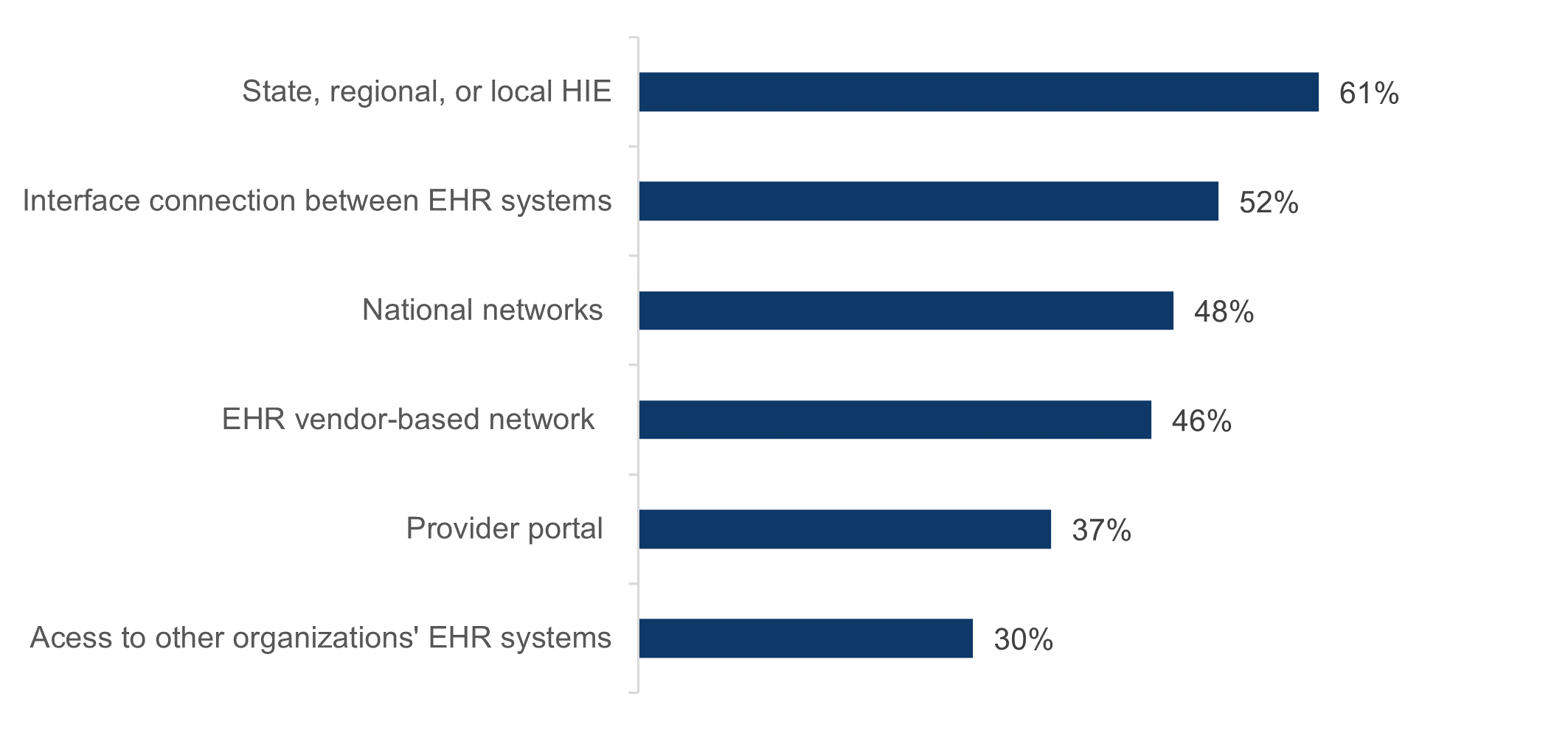

Over 60 percent of hospitals used an HIE to electronically query or find patient health information from external sources in 2021.

Findings

- Over 45 percent of hospitals used national networks, interface connections between EHRs, or EHR-vendor based networks to query patient health information from external sources.

- Access to other organizations’ EHR systems using login credentials remained the least commonly used method for querying patient information.

Figure 3: Methods used by hospitals to electronically find (or query) patients’ health information, 2021.

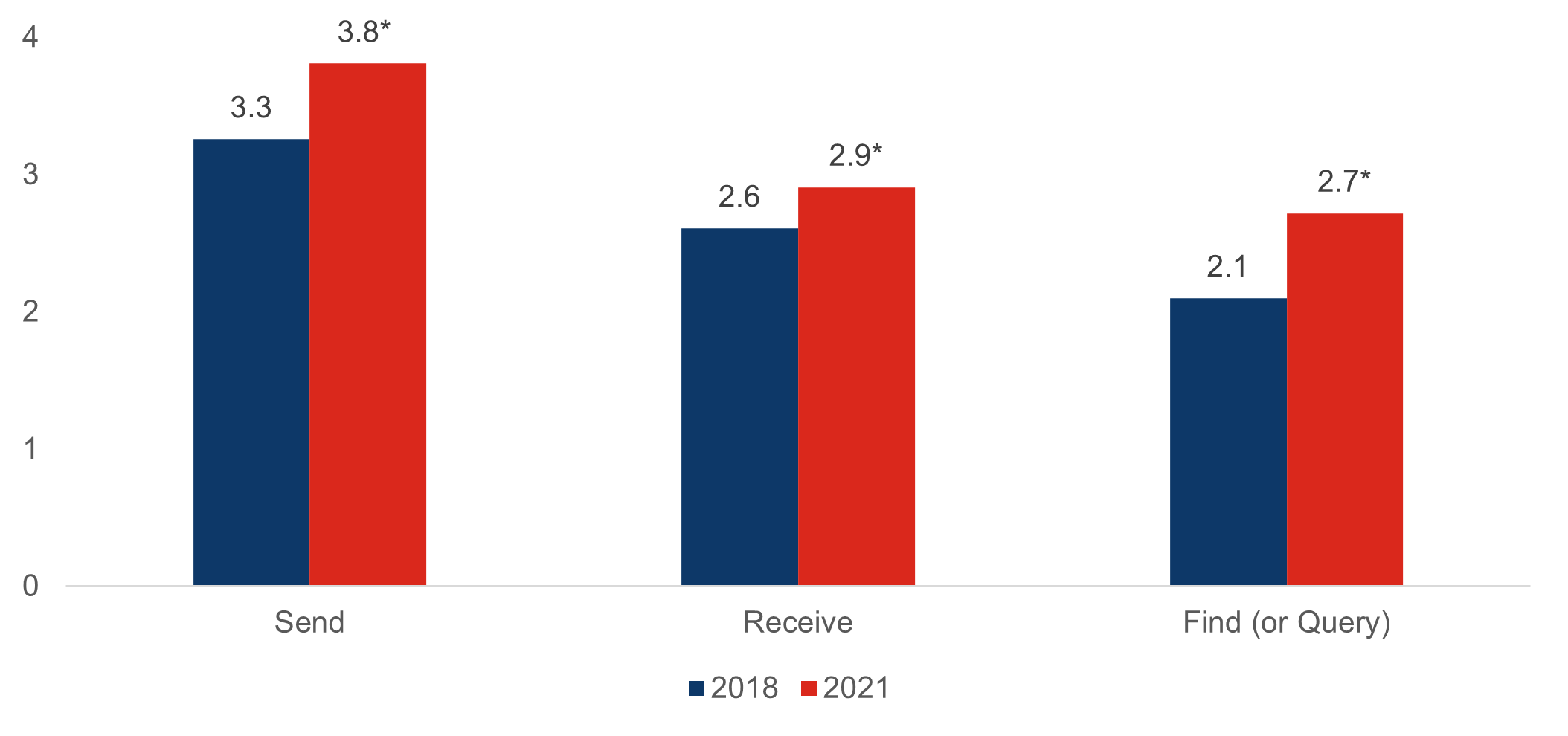

The average number of methods hospitals used for electronically sending, receiving, and finding patient health information from external sources increased between 2018 and 2021.

Findings

- On average, in 2021 hospitals used about three methods (out of 7 possible methods) for receiving summary of care records.

- On average, in 2021 hospitals used more methods (3.8) for electronically sending summary of care records and fewer methods for electronically finding or querying (2.7) patient health information.

Figure 4: Average number of electronic methods hospitals used to send, receive, and find (or query) health information, 2018 and 2021.

Notes: *Significantly different from 2018 within a corresponding category (p<0.05).

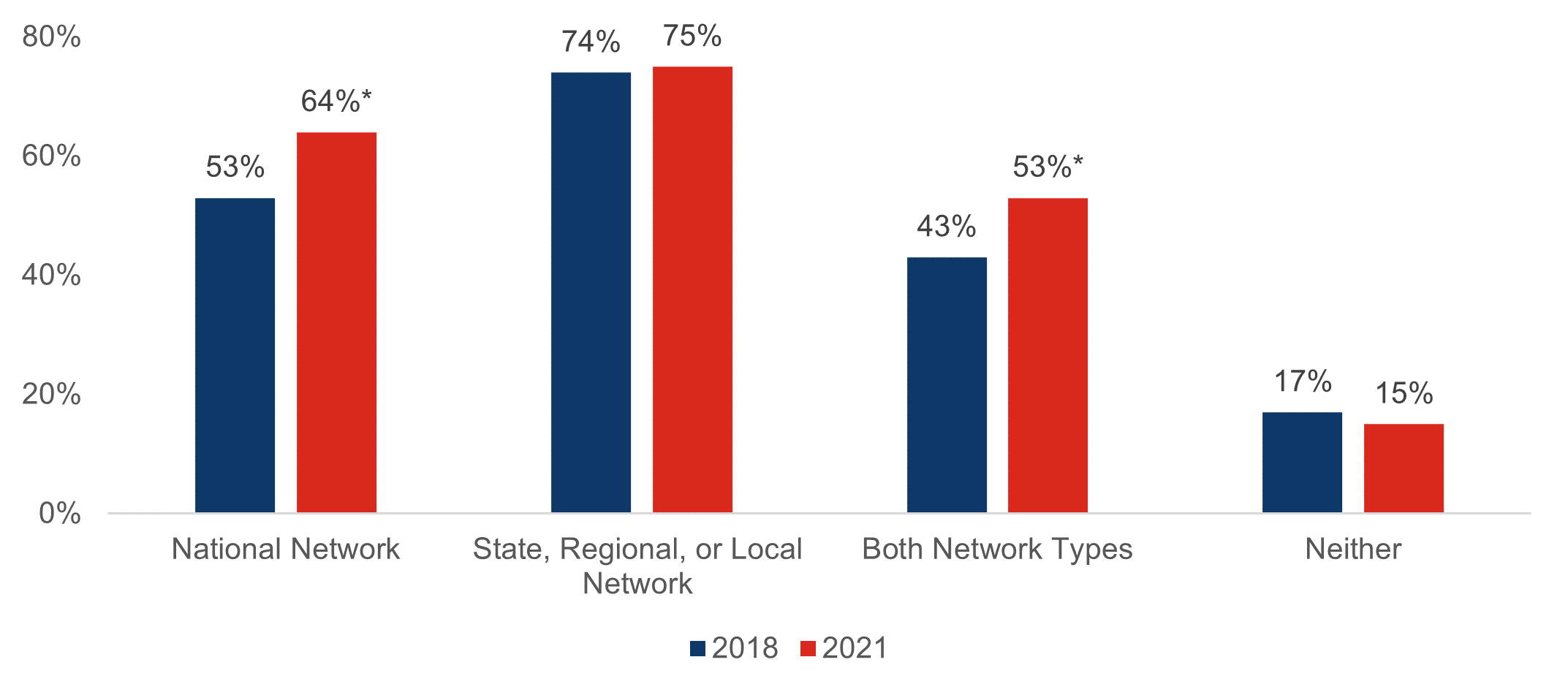

Hospital participation rates in state, regional, or local network remained high, at about 75 percent in 2021.

Findings

- The percent of hospitals participating in both national and state, regional, or local networks increased from 53% to 64% between 2018 to 2021.

- Less than 1 in 5 hospitals chose not to participate in either national network or state, regional, or local networks in 2021. There is no difference compared to 2018.

Figure 5: Percent of hospitals that participate in national and state, regional, or local health information networks, 2018- 2021.

Notes: National network consists of hospital participation in CommonWell Health Alliance, e-Health Exchange, Sequoia Project’s Carequality, Strategic Health Information Exchange Collaborative (SHIEC), as well as EHR vendor’s network. *Significantly different from 2018 within a corresponding category. (p<0.05).

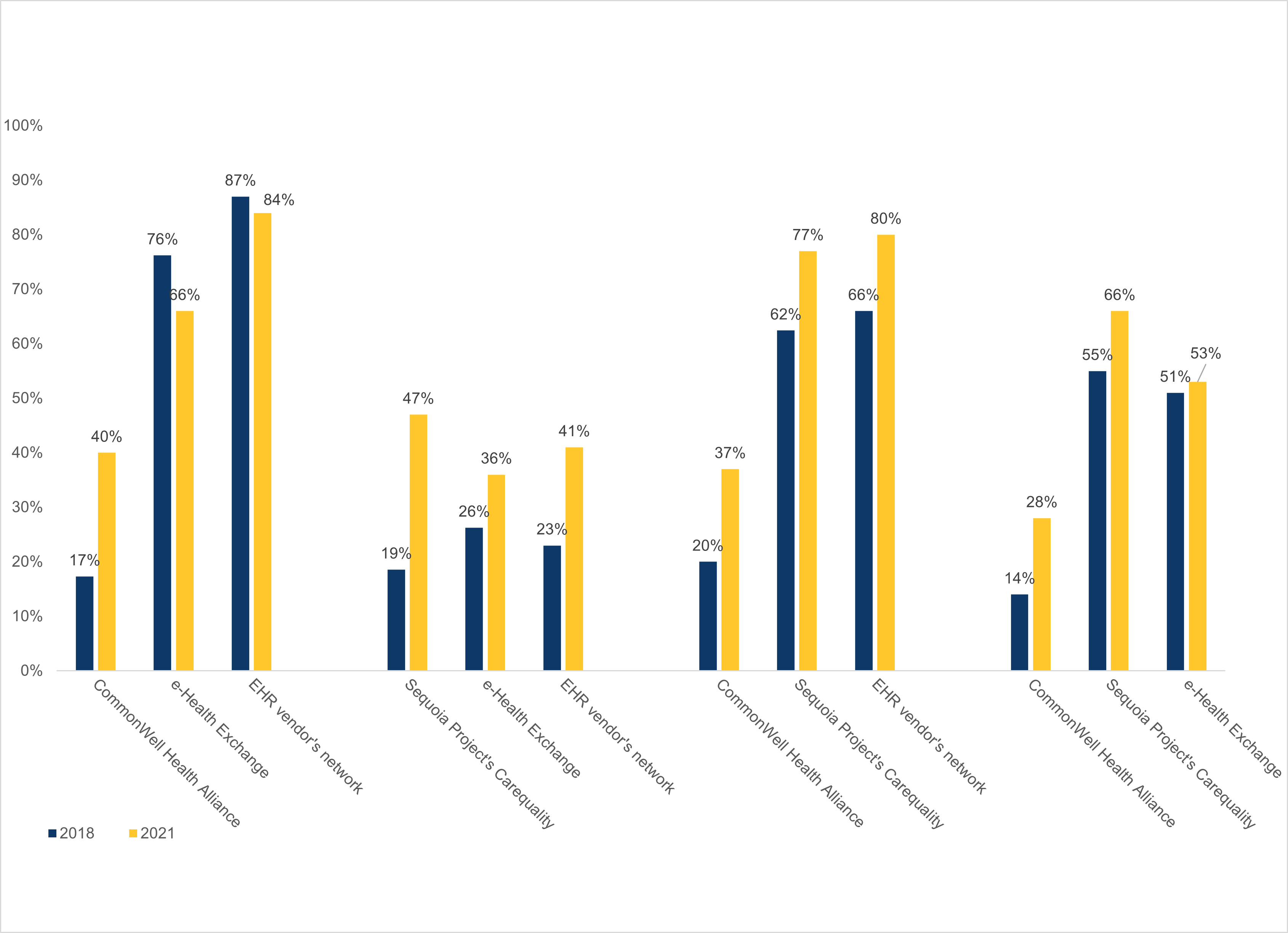

Hospital participation in CommonWell Health and Sequoia Project’s Carequality significantly increased between 2018 and 2021.

Findings

- Hospital participation in Carequality increased by 14 percentage points, the largest increase among national networks.

- In addition to the four networks below, in 2021, 90% of hospitals participated in Direct messaging enabled by the Direct Protocol and the DirectTrust.

Table 4: Hospital participation in query-based national networks, 2018-2021.

| National Network | 2018 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| CommonWell Health Alliance | 19% | 29%* |

| e-Health Exchange | 25% | 29% |

| Sequoia Project’s Carequality | 20% | 34%* |

| EHR vendor’s network | 32% | 43%* |

Notes: *Significantly different from 2018 (p<0.001).

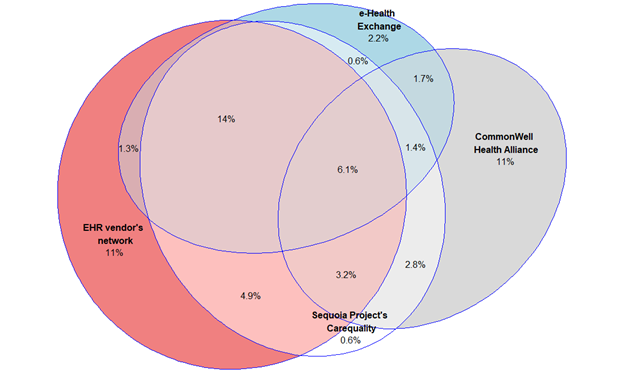

In 2021, about 4 in 10 (39%) hospitals reported participating in more than one of four measured national networks.

Findings

- Eleven percent of hospitals reported only participating in CommonWell Health Alliance and no other national network.

- There were few hospitals (0.6%) that only participate in Carequality and no other national network, consistent with its role as a framework.

Figure 6: Relationship between participation in each national network in 2021.

Notes: Figure does not include 37% of hospitals that did not participate in a national network. See Appendix Figure for a simplified exposition of these relationships.

Summary

Interoperability continues to improve among hospitals. As of 2021, 88% of hospital engaged in electronically sending and obtaining patient health information, through either querying or electronically receiving summary of care records. The number of hospitals engaged in integrating patient health information into EHRs grew by 40% since 2017, with about three-quarters of hospitals engaging in this activity in 2021. These trends show progress in interoperable exchange.

Progress has been made in the rate at which hospitals report providers have electronic patient health information available at the point of care and use that information during 2017-2021. Rural and small hospitals’ rates of having information available at the point of care increased by over 26% reaching 48% in 2021, and nationally it grew over 20%, reaching 62% in 2021. Additionally, usage of information received electronically from outside sources by rural and small hospitals increased at twice the rate of hospitals nationally (over 40% vs. over 20%) between 2017 and 2021. Yet, these less resourced hospitals are still not on par with their counterparts, indicating the need to continue addressing challenges with having full access to electronic information from external sources.

Hospitals’ rapid improvements in interoperability could be attributed in part to the initial implementation of health IT provisions from the ONC Cures Act Final Rule (Cures Rule) and adoption of 2015 Edition certified technology. The Cures Rule updated the Health IT Certification Program to include new and updated criteria and standards that will advance interoperability. Nearly 90% of hospitals have adopted 2015 Edition certified technology and are well positioned to adopt these new and updated criteria and standards. Other data show that a large majority of hospitals have already done so (6). Additionally, seventy-four percent of hospitals adopted the bulk data export capability, as of 2021. The most common uses of bulk data export were for analytics and reporting (63%) and population and health management (35%), and, less so, for switching EHRs (12%).

Hospitals continued to use a variety of electronic exchange methods to achieve progress in interoperability. Compared to 2018, in 2021 hospitals were using more methods to send (3.8 out of 7), receive (2.9 out of 7) summary of care records, and find (2.7 out of 6) patient health information. The use of HISPs and HIEs were the most commonly used electronic methods for sending and receiving information. The use of HIEs and interface connections with EHRs were the most commonly used methods for finding patient health information. About 4 in 10 hospitals continued to participate in multiple networks, indicating possible challenges to exchange across different networks and thus reinforcing the need for having multiple networks. Policy activities that support cross-network exchange such as Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) will help reduce the number of different networks and methods that hospitals need to use to support exchange.

Launched in early 2022, TEFCA aims to establish a universal policy and technical floor for nationwide interoperability and simplify connectivity for organizations to securely exchange information (7). Other provisions of the Cures Rule are being implemented now to help hospitals shift from simply establishing connectivity to optimizing and simplifying the use of multiple methods of exchanging information. However, some barriers to information exchange remain prevalent. For instance, 48% of hospitals reported one-sided sharing relationships in which they share patient data with other providers who do not in turn share patient data with the hospital (Appendix Table).

Given that a majority of hospitals (74%) reported the ability to integrate information into their EHRs, current policy efforts could increase the value of that integration. For instance, recent actions were taken to improve the quality of data from external sources by advancing the use of specific data elements, such as through the United States Core Data for Interoperability (USCDI), and through the required use of standardized application programming interface (API) technology using the HL7 Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR). Efforts such as these should help ensure that information is available, integrated into the EHR, and used at the point of care – all of which have further room for improvement and will ultimately drive improvements in care and secondary use of data, such as for research.

Definitions

Non-federal acute care hospital: Hospitals that meet the following criteria: acute care general medical and surgical, children’s general, and cancer hospitals owned by private/not-for-profit, investor-owned/for-profit, or state/local government and located within the 50 states and District of Columbia.

Interoperability: The ability of a system to exchange electronic health information with and use electronic health information from other systems without special effort on the part of the user. This brief further specifies interoperability as the ability for health systems to electronically send, receive, find, and integrate health information with other electronic systems outside their organization.

Integrate: Whether the EHR integrates summary of care record received electronically (not eFax) from providers or sources outside your hospital system/organization without the need for manual entry.

Find: Whether providers at your hospital query electronically for patients’ health information (e.g., medications, outside encounters) from sources outside of your organization or hospital system.

Small hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals of bed sizes of 100 or less.

Rural hospital: Hospitals located in a non-metropolitan statistical area.

Critical Access Hospital: Hospitals with less than 25 beds and at least 35 miles away from another general or critical access hospital.

Health information exchange (HIE): State, regional, or local health information network. This does not include local proprietary or enterprise networks.

Health information service provider (HISP): HISPs are network service operators that enable nationwide clinical data exchange using Direct Secure Messaging.

National network: Health information networks that are nationwide in scope. This includes multi-EHR vendor networks (e.g. Commonwell or e-Health Exchange) which can be used to exchange health information either directly through an EHR or health information exchange (HIE) vendor.

2015 Edition Certified Electronic Health Record (EHR) Technology: An EHR system that meets certification criteria requirements established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. These criteria establish the required capabilities, standards, and implementation specifications that health information technology needs to meet in order to become certified under the ONC Health IT Certification Program. Certified health IT products can be used for participation in CMS quality reporting programs and State Promoting Interoperability Programs.

Data sources and methods

Data are from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Information Technology (IT) Supplement to the AHA Annual Survey. Since 2008, ONC has partnered with the AHA to measure the adoption and use of health IT in U.S. hospitals. ONC funded the AHA IT Supplement to track hospital adoption and use of EHRs and the exchange of clinical data.

The chief executive officer of each U.S. hospital was invited to participate in the survey regardless of AHA membership status. The person most knowledgeable about the hospital’s health IT (typically the chief information officer) was requested to provide the information via a mail survey or secure online site. Non-respondents received follow-up mailings and phone calls to encourage response.

This brief reports results from the 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 AHA IT Supplement. The 2017 survey was fielded from January 2018 to May 2018; the 2018 survey was fielded from January 2019 to May 2019; and the 2019 survey was fielded from January 2020 to June 2020. Due to pandemic-related delays, the 2020 survey was not fielded on time and was fielded from April 2021 to September 2021. Since the IT supplement survey instructed respondents to answer questions as of the day the survey is completed, we refer to responses to the 2020 IT supplement survey as happening in 2021 in this brief. The response rate for non-federal acute care hospitals for the 2020 survey was 54 percent. A logistic regression model was used to predict the propensity of survey response as a function of hospital characteristics, including size, ownership, teaching status, system membership, and availability of a cardiac intensive care unit, urban status, and region. Hospital-level weights were derived by the inverse of the predicted propensity.

References

- Brenner SK, Kaushal R, Grin span Z, et al. Effects of health information technology on patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016; 23:1016-36.

- Walker DM. Hospital efficiency gains from health information exchange participation. Health Care Management Science. 2017DOI: 10.1007/s10729-017-9397-4.

- Richardson, J., E. Abramson, and R. Kaushal. 2012. The value of health information exchange. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, pp. 17-24.

- 21st Century Cures Act. H.R. 34, 114th Congress. 2016. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-114hr34enr/pdf/BILLS-114hr34enr.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2021.

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ‘Interoperability’. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/interoperability. Accessed: October 5, 2022.

- Posnack S. & Barker W. ‘The Heat is On: US Caught FHIR in 2019.’ ONC Buzz Blog. https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/health-it/the-heat-is-on-us-caught-fhir-in-2019.

- Tripathi M. & Yeager M. ‘3-2-1. TEFCA is Go for Launch.’ ONC Buzz Blog. https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/interoperability/321tefca-is-go-for-launch.

Suggested Citation

Pylypchuk Y., J. Everson. (January 2023). Interoperability and Methods of Exchange among Hospitals in 2021. ONC Data Brief, no. 64. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC.

Appendix

Appendix Table: Percent of hospitals that experienced barriers when trying to electronically send, receive, or find health information to/from other care settings or organizations, 2021.

| Percent | |

|---|---|

| Barriers related to electronically sending patient health information | |

| Exchange partners’ we would like to send data to do not have an EHR or other electronic system to receive data | 52% |

| Exchange partners’ EHR system lacks capability to receive data | 64% |

| Difficult to find providers’ Direct address | 70% |

| Many recipients of care summaries report that the information is not useful | 38% |

| Cumbersome workflow to send the information from our EHR system | 28% |

| Difficult to locate Direct address of a provider | 61% |

| Receive error message when sending Direct messages to recipients | 15% |

| Barriers related to electronically receiving patient health information | |

| Difficult to match or identify the correct patient between systems | 57% |

| There are providers whom we share patients with that don’t typically exchange patient data with us | 67% |

| There are providers whom we electronically share patient information with that don’t typically share patient information with us | 48% |

| There are providers who share data with us but do not provide that data in the format that we request | 36% |

| There are providers who state that they cannot exchange information with us due to privacy laws (e.g. HIPAA) in situations where that does not seem appropriate | 9% |

| Other barriers related to exchanging patient health information | |

| Greater challenges exchanging data across different vendor platforms | 72% |

| Paying additional costs to exchange with organizations outside our system | 43% |

| Develop customized interfaces in order to electronically exchange health information | 54% |

| Contractual constraints between healthcare providers and health vendors limit our ability to exchange data with providers using certain systems | 24% |

Appendix Figure: Relationship between participation in each national network in 2018-2021.