An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov

website belongs to an official government organization in the

United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock

(

) or

https://

means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.

Interoperable Exchange of Patient Health Information Among U.S. Hospitals: 2023

No. 71 | May 2024

- Interoperable Exchange of Patient Health Information Among U.S. Hospitals: 2023 [PDF – 412.83 KB]

- Data Brief 71 Figure 1 [PNG – 99.56 KB]

- Data Brief 71 Figure 2 [PNG – 23.62 KB]

- Data Brief 71 Figure 3 [PNG – 48.38 KB]

- Data Brief 71 Figure 4 [PNG – 41.78 KB]

- Data Brief 71 Figure 5 [PNG – 24.25 KB]

- Data Brief 71 Figure 6 [PNG – 66.04 KB]

Seamless interoperable health information exchange between disparate organizations across the health care continuum is crucial to ensure clinicians have access to the most timely and relevent patient health information when making healthcare decisions. Hospitals play an important role in interoperable exchange, and, since 2014, ONC has tracked hospitals’ overall engagement in four domains of interoperable exchange (send, receive, find, and integrate) to measure the effects of federal policy and industry efforts on interoperability (1,2). As a greater share of hospitals engaged in interoperable exchange at least sometimes – 70% of hospitals as of 2023 – this data brief seeks to examine this more granularly and raise the bar. Therefore, this brief reports the share of U.S. hospitals that reported they routinely engaged in interoperable exchange in 2023, as this is a goal of government and industry efforts. In addition, this brief describes the breadth of electronic information exchange between hospitals and other providers across the care continuum and focuses on how often clinicians in these hospitals routinely use this information at the point of care.

Highlights

- In total, 70% of non-federal acute care hospitals engaged in all domains of interoperable exchange (send, find, receive, and integrate) routinely or sometimes in 2023.

- While hospitals routinely engaged in interoperable exchange increased by 54 percent since 2018, less than half of hospitals (43%) routinely engaged in interoperable exchange, while 27% sometimes engaged in interoperable exchange.

- From 2018 to 2023, hospitals increased routine engagement in all four interoperable exchange domains.

- Lower-resourced hospitals (i.e., small, rural, critical access, or independent) engaged less frequently in interoperable exchange when compared to their higher-resourced counterparts.

- Seventy-one percent of hospitals reported routine access to necessary clinical information from outside providers, but less than half (42%) indicated that clinicians routinely use it when treating patients.

- Only 16% of hospitals reported sending summary of care records to most or all long-term/post-acute care providers and 17% reported sending summary of care records to most or all behavioral health providers.

In 2023, 70% of hospitals engaged in all four domains of interoperable exchange, maintaining the same level from 2022 to 2023.

Findings

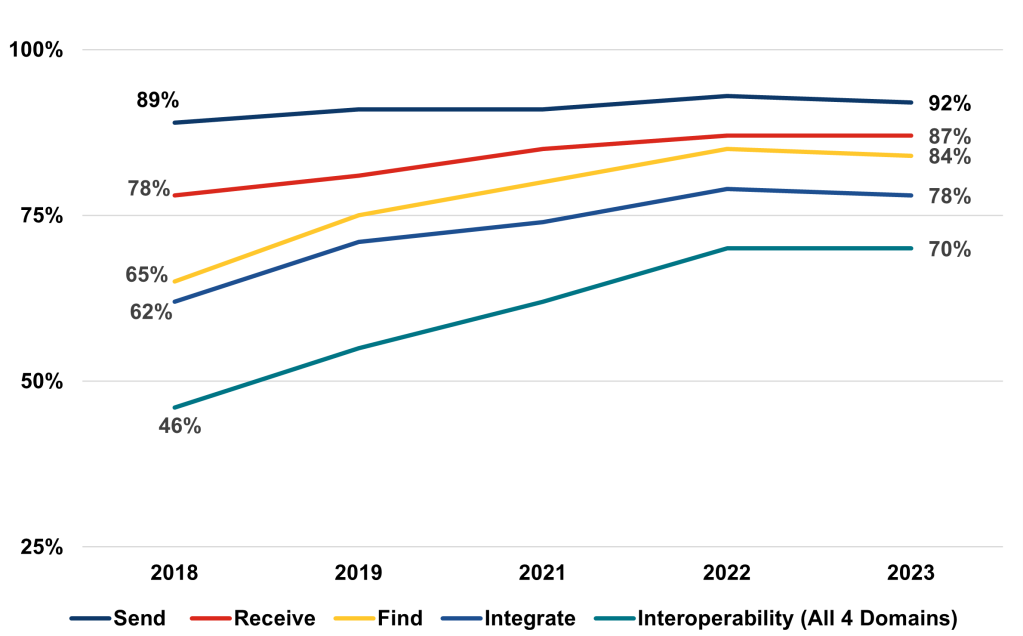

- Hospitals’ engagement in all four domains of interoperability (send, receive, find, and integrate) increased from 46% in 2018 to 70% in 2023, a 52% increase.

- While almost all hospitals electronically send patient health information, about three-quarters integrate the information they receive within electronic health records.

Figure 1: Percent of U.S. Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals Engaged in Interoperable Exchange of Electronic Health Information: 2018-2023.

Notes: Study population are non-federal acute care hospitals. Please refer to the Definitions and Methods sections of this brief for more information. Please see full trend graph from 2014 to 2023 available here: https://www.healthit.gov/data/quickstats/electronic-health-information-exchange-hospitals

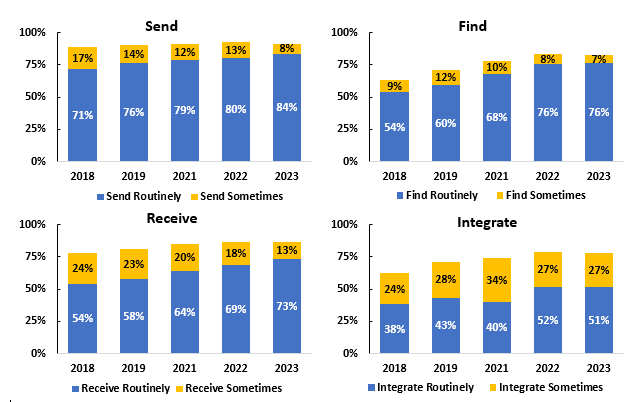

From 2018 to 2023, hospitals increased routine engagement in all four interoperable exchange domains.

Findings

- Hospitals’ rates of often sending information to external providers increased from 71% to 84% between 2018 and 2023, while rates of those sometimes sending decreased from 17% to 8%.

- Hospitals’ rates of often receiving information from external providers increased from 54% to 73% between 2018 and 2023, while rates of those sometimes receiving decreased from 24% to 13%.

Figure 2: Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals’ Frequency of Engagement in Interoperable Exchange: 2018-2023

Notes: Data not shown for those hospitals that reported being rarely or never interoperable. Please see Definitions and Methods sections of this brief for more information.

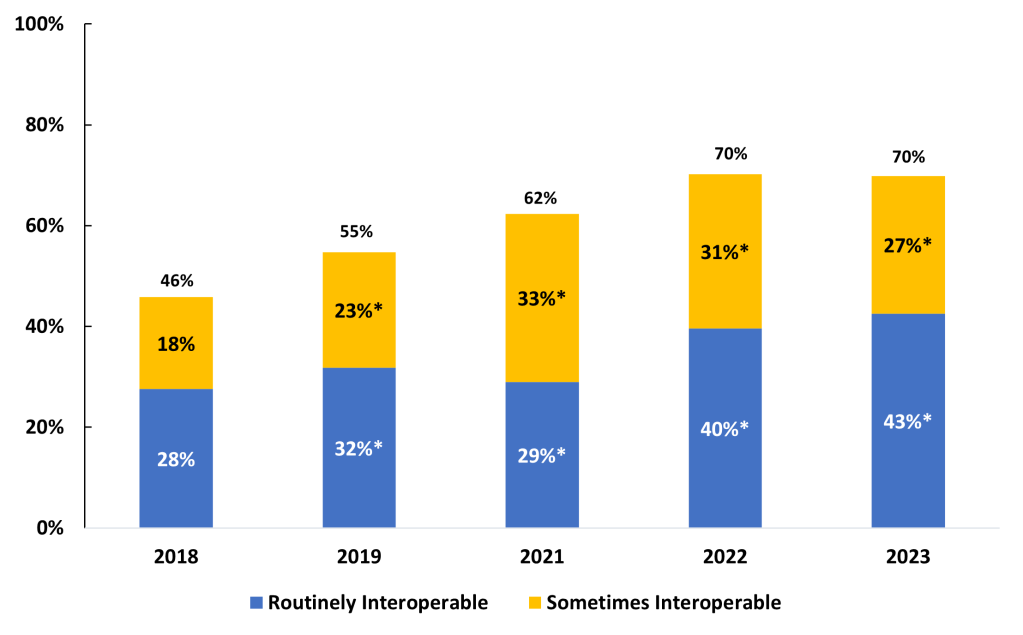

From 2018 to 2023, hospitals routinely engaging in interoperable exchange increased by 54 percent.

Findings

- The percent of hospitals that routinely engaged in all four domains of interoperable exchange increased from 28% in 2018 to 43% in 2023.

- In contrast, the percent of hospitals sometimes engaged in interoperable exchange increased from 2018 to 2020 and then declined from 2020 to 2023.

Figure 3: Engagement with and Frequency of Interoperable Exchange Among Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals from 2018 to 2023

Notes: Routinely interoperable refers to hospitals that often find, send, receive, and routinely integrate electronic health information from outside sources. Sometimes interoperable refers to hospitals that find, send, receive electronic information often or sometimes and integrate electronic health information, but not routinely. Please see Definitions and Methods sections of this brief for more information. *significantly different from previous year (p<0.05).

A greater share of higher-resourced hospitals reported routine engagement in all 4 domains of interoperable exchange.

Findings

- Over half (53%) of system-affiliated hospitals routinely engaged in all 4 domains of interoperable exchange compared to just 22% of independent hospitals.

- Over half (55%) of independent hospitals were not fully engaged in all 4 domains of interoperable exchange.

- 53% of large hospitals reported routinely engaging in all 4 domains of interoperable exchange compared to 38% of small hospitals. In comparison, 30% of large hospitals reported sometimes engaging in interoperable exchange compared to 23% of small hospitals.

- As of 2023, about 2 in 5 rural and critical access hospitals were not fully interoperable, and therefore did not at least sometimes engage in all 4 domains of interoperable exchange

Table 1: Interoperability Frequency Among Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals by Hospital Characteristics: 2023

| Hospital Characteristics | Routinely Interoperable | Sometimes Interoperable | Not Fully Interoperable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Interoperability | 43% | 27% | 30% |

| Small | 38% | 23% | 39% |

| Medium | 46%* | 33%* | 21%* |

| Large | 53%* | 30%* | 17%* |

| Independent | 22% | 23% | 55% |

| System Affiliated | 53%* | 29% | 18%* |

| Rural | 36% | 23% | 41% |

| Urban | 47%* | 30%* | 23%* |

| Critical Access Hospital (CAH) | 37% | 22% | 42% |

| Non-CAH | 45%* | 30%* | 25%* |

Notes: CAH=Critical Access Hospital. Routinely interoperable refers to hospitals that often find, send, receive, and routinely integrate electronic health information from outside sources. Sometimes interoperable refers to hospitals that find, send, receive electronic information often or sometimes and integrate electronic health information, but not routinely. Not interoperable refers to hospitals that did not did not often or sometimes find, send, and receive electronic health information and did not report integrating electronic health information from outside sources. Please see Definitions for detailed definitions. *Significantly different within column from reference category (small, independent, rural, CAH) (p<0.05).

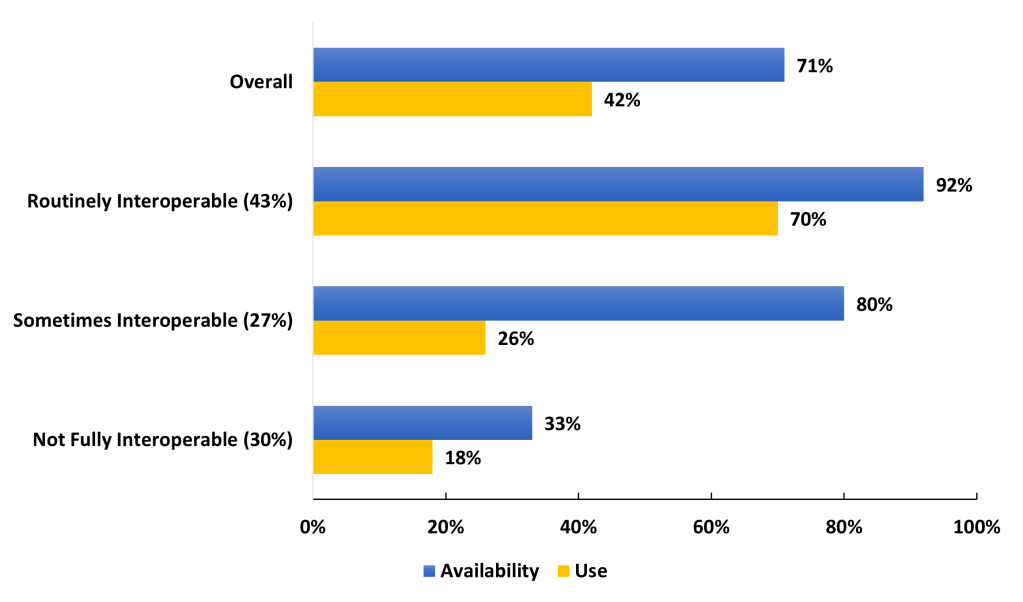

Hospitals that routinely engaged in all 4 domains of interoperable exchange more often reported routine access and use of patient health information from outside providers.

Findings

- Overall in 2023, 71% of hospitals routinely had access to necessary clinical information available electronically from outside providers at the point of care, but only 42% of clinicians often used that information.

- A majority of hospitals engaged in interoperable exchange reported their clinicians had routine access to patient health information from outside organizations (92% of routinely interoperable hospitals and 80% of sometimes interoperable hospitals).

- 70% of hospitals that routinely engaged in interoperable exchange reported that clinicians often used clinical information available electronically from outside providers when treating patients, compared with 26% of hospitals that sometimes engaged in interoperable exchange.

Figure 4: Availability and Use of Electronic Patient Health Information from External Providers at the Point of Care at Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals, 2023

Notes: Availability refers to those hospitals that reported routinely having necessary clinical information available electronically from external providers at the point of care. Use refers to hospitals that often use patient health information received electronically from external providers at the point of care. External providers may include hospitals, ambulatory care providers, long-term post-acute care providers, or behavioral health providers outside of a hospital’s system. Please see Definitions for more information.

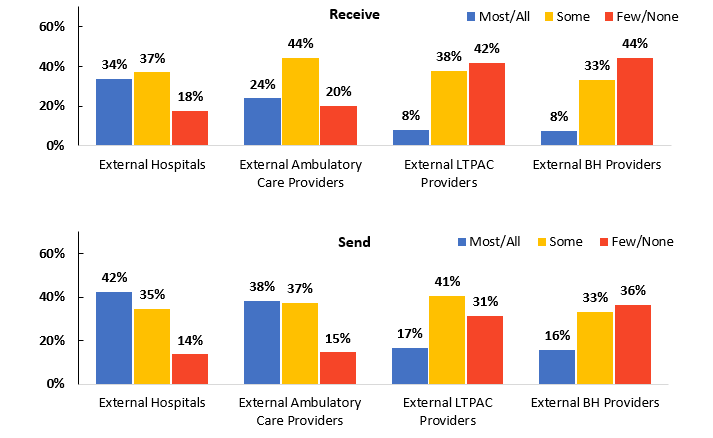

In 2023, hospitals reported electronic exchange with external hospitals and ambulatory care providers more often than with external long-term post-acute care and behavioral health providers.

Findings

- While 84% of hospitals reported that they routinely send electronic health information (see Figure 2), only 42% reported that they send summary of care documents to most or all external hospitals and only 38% reported that they send that information to most or all external ambulatory care providers.

- Hospitals reported sending information to long-term post-acute care providers at twice the rate (17%) as receiving information from long-term post-acute care providers (8%), with similar trends for behavioral health providers.

Figure 5: Ability of Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals to Electronically Share (Send and Receive) Summary of Care Records with Outside Providers: 2023

Notes: Data not shown for those hospitals who responded ‘do not know’ or were missing a response. LTPAC = long-term post-acute care and BH = behavioral health. Please see Definitions for detailed definitions.

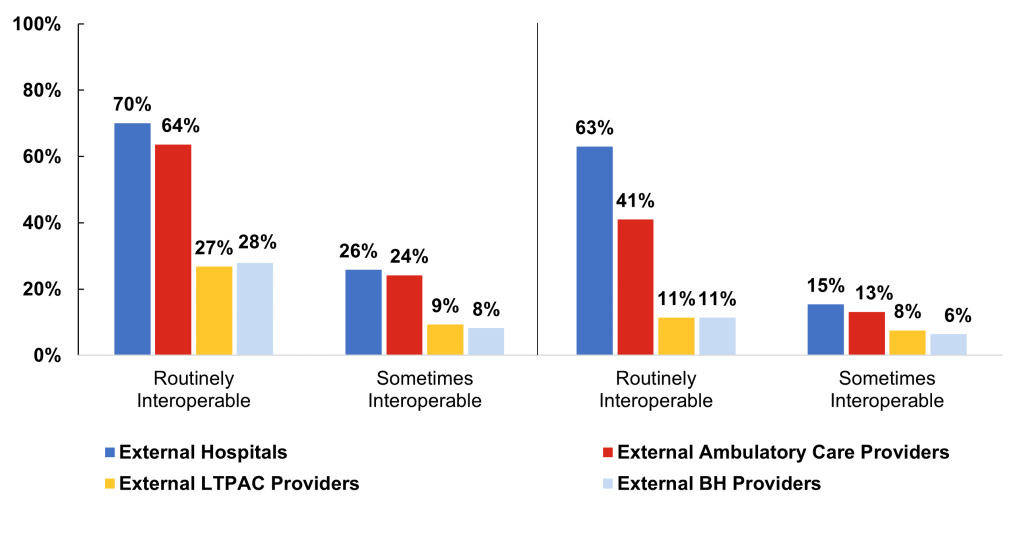

Hospitals that routinely engaged in interoperable exchange had greater breadth of exchange with external hospitals and ambulatory care, long-term post-acute care, and behavioral health providers.

Findings

- Most hospitals routinely engaged in interoperable exchange sent (70%) and received (63%) electronic summary of care records from most or all external hospitals and ambulatory care providers, while those that were sometimes interoperable shared with less external providers.

- Despite high levels of engagement in interoperable exchange, only about a quarter of hospitals that were routinely interoperable across all 4 domains sent electronic summary of care records to most or all external long-term post-acute care and behavioral health providers, with even less sharing reported among those that were sometimes interoperable.

Figure 6: Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals’ Engagement in Electronic Summary of Care Record Sharing with Most or All External Providers: 2023

Notes: Data include hospitals that reported receiving from or sending electronic summary of care records to all or most outside providers. LTPAC = long-term post-acute care and BH = behavioral health. Please see Definitions for detailed definitions. Sharing among not interoperable hospitals not shown.

Summary

This brief explores the current state of interoperability among non-federal acute care hospitals, focusing on hospitals’ frequency of engaging in the four domains of interoperable exchange that ONC has tracked for several years. The successful uptake of interoperable technology drove this approach: from 2018 to 2023, the percent of hospitals that reported at least sometimes engaging in each interoperability domain (find, send, receive, integrate) increased to between 78 and 92%. It is therefore necessary to ‘raise the bar’ to focus on often or routine interoperable exchange to continue to assess progress in interoperability. This focus demonstrated that hospitals shifted from sometimes engaging in interoperability to routinely engaging in interoperability between 2021 and 2023. The percent of hospitals routinely engaging in interoperable exchange increased substantially (from 29 to 43%), while hospitals reporting sometimes interoperable exchange declined from 33 to 27%.

Underscoring the complexity of achieving interoperable exchange, the resources available to hospitals play a crucial role in interoperability engagement, with larger, urban, and system-affiliated hospitals demonstrating higher rates of engaging in routine interoperability across all four domains compared to their smaller, rural, and independent counterparts. Half (53%) of large hospitals often or routinely engaged in interoperable exchange compared to 38% of small hospitals. Furthermore, system-affiliated hospitals also reported higher rates of interoperability compared to independent hospitals, with 53% routinely engaging in interoperable exchange compared with 22% of independent hospitals. Similarly, urban hospitals more frequently engaged in routine interoperable exchange (47% were routinely interoperable) than their rural counterparts (36% were routinely interoperable).

The availability and use of patient health information at the point of care was higher among hospitals that routinely engaged in interoperable exchange across all four domains, emphasizing the importance of routine interoperability in ensuring information is used to support clinical decision-making and patient care outcomes. Overall, in 2023, 71% of hospitals routinely had access to necessary clinical information available electronically from external providers at the point of care and 42% of hospitals often used that information. Hospitals that routinely engaged in interoperable exchange across all four domains had higher rates of patient health information availability (92%) and use at the point of care (70%) compared to those only sometimes engaged or not engaged in interoperable exchange. Among hospitals that were sometimes interoperable or not interoperable, 26% and 18%, respectively, used information electronically received at the point of care.

Despite this success, relatively few hospitals reported exchanging electronic summary of care documents with most external providers. A substantial percent of hospitals—but far short of a majority—reported sharing care summaries with most or all external hospitals and ambulatory care providers. In contrast, few hospitals—even those that reported routine interoperable exchange—reported exchanging information with most long-term and post-acute care (LTPAC) and behavioral health providers. These differences in data exchange with external providers likely reflect a combination of limited exchange capabilities of LTPAC and behavioral health providers and that hospitals may be largely focused on exchange with their main data partners, which likely are other hospitals and ambulatory care providers. At larger health systems, much of the exchange may be occurring internally among participating providers.

These findings suggest an ongoing need for comprehensive engagement in interoperability across the healthcare continuum. While the adoption of certified health IT by hospitals and physician practices has improved interoperability, achieving nationwide routine interoperable exchange will require additional efforts, as indicated by the certification requirements for health IT aimed at enhancing this exchange (3). Additionally, the Health Information Technology Advisory Committee (HITAC) emphasizes the importance of addressing these interoperability gaps across the care continuum to advance the use of technologies that bolster interoperability, which is crucial for realizing the full potential of health IT tools in transforming the entire healthcare sector (4). To address these gaps, initiatives such as the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) are aimed at improving connectivity and minimizing barriers to data exchange are steps forward to help support equitable access to and use of patient health information (5). The data also highlight that targeted efforts to support fit-for-purpose initiatives that increase interoperability among LTPAC and behavioral health providers, such as the recently announced Behavioral Health IT Initiative (6).

This brief showcases the value of tracking the frequency of exchange, breadth of exchange partners, and use of information at the point of care to measure achievement of widespread interoperable exchange. Continued, comprehensive measurement of interoperability will help inform progress and future efforts, as well as help evaluate policy impacts.

Definitions

Critical Access Hospital: Hospitals with less than 25 beds and at least 35 miles away from another general or critical access hospital.

Find: Whether providers at your hospital query electronically for patients’ health information (e.g., medications, outside encounters) from sources outside of your organization or hospital system.

Integrate: Whether the electronic health record integrates summary of care record received electronically (not eFax) from providers or sources outside your hospital system/organization without the need for manual entry.

Sometimes Interoperable: Non-federal acute care hospitals were not routinely interoperable, and therefore reported finding, sending, receiving electronic patient health information often or sometimes, and integrating (but not routinely) electronic patient health information from sources outside their hospital or hospital system.

Interoperability: The ability of a system to exchange electronic health information with and use electronic health information from other systems without special effort on the part of the user. This brief further specifies interoperability as the ability for health systems to electronically send, receive, find, and integrate health information from electronic systems outside their organization.

Non-federal acute care hospital: Hospitals that meet the following criteria: acute care general medical and surgical, children’s general, and cancer hospitals owned by private/not-for-profit, investor-owned/for-profit, or state/local government and located within the 50 states and District of Columbia.

Not Fully Interoperable: Non-federal acute care hospitals that reported rarely or never finding, sending, and receiving electronic health information and did not integrate electronic patient health information from sources outside their hospital or hospital system.

Receive: Whether providers at your hospital receive a summary of care record electronically (not eFax) from providers or sources outside your hospital system/organization.

Routinely Interoperable: Non-federal acute care hospitals that were routinely or often interoperable, and reported they often find, often send, often receive, and routinely integrate electronic patient health information from sources outside their hospital or hospital system.

Rural hospital: Hospitals located in a non-metropolitan core-based statistical area

Large hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals of bed sizes of 400 or more.

Medium hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals of bed sizes of 100-399.

Send: Whether providers at your hospital sends a summary of care record electronically (not eFax) when a patient transitions to another care setting outside of your hospital system/organization.

Small hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals of bed sizes of 100 or less

System-affiliated hospital: A system is defined as either a multi-hospital or a diversified single hospital system. A multi-hospital system is two or more hospitals owned, leased, sponsored, or contract managed by a central organization. Single, freestanding hospitals may be categorized as a system by bringing into membership three or more, and at least 25 percent, of their owned or leased non-hospital pre-acute or post-acute health care organizations.

Data Sources and Methods

Data are from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Information Technology (IT) Supplement to the AHA Annual Survey. Since 2008, ONC has partnered with the AHA to measure adoption and use of health IT in U.S. hospitals. ONC funded the 2023 AHA IT Supplement to track hospital reported adoption and use of electronic health records (EHRs) and the exchange of clinical data.

The chief executive officer of each U.S. hospital was invited to participate in the survey regardless of AHA membership status. The person most knowledgeable about the hospital’s health IT (typically the chief information officer) was requested to provide the information via a mail survey or secure online site. Non respondents received follow-up mailings and phone calls to encourage response.

This brief reports results from the 2018-2023 AHA IT Supplement. The 2018 survey was fielded from January 2019 to May 2019; and the 2019 survey was fielded from January 2020 to June 2020. Due to pandemic-related delays, the 2020 survey was not fielded on time and was fielded from April 2021 to September 2021; the 2022 survey was fielded from July 2022 to December 2022; and the 2023 survey was fielded from March 2023 to August 2023. Since the IT supplement survey instructed respondents to answer questions as of the day the survey is completed, we refer to responses to the 2020 IT supplement survey as happening in 2021 in this brief. Of note, the 2022 and 2023 surveys were fielded relatively close together (July to December 2022 and March to August 2023) to catch up from pandemic-related delays. For the 2023 survey, the response rate for non-federal acute care hospitals (N = 2,547) was 58% percent.

A logistic regression model was used to predict the propensity of survey response as a function of hospital characteristics, including size, ownership, teaching status, system membership, and availability of a cardiac intensive care unit, urban status, and region. Hospital-level weights were derived by the inverse of the predicted propensity.

The interoperability metric used by ONC is used to understand the current state of health IT adoption and to identify areas in which improvements can be made. This metric comprises the ability to send, find, receive, and integrate information electronically from outside sources. Those hospitals with responses of rarely, no, do not know, or not applicable were coded as no. In 2023, 8% of hospitals did not send, 18% of hospitals did not find, 14% of hospitals did not receive, and 22% of hospitals did not integrate electronic health information.

For the send domain, hospital representatives were asked if they send summary of care records electronically using methods such as provider portals, interface connections between EHR systems, login credentials that allow access to an EHR, HISPs that enable messaging via DIRECT protocol, health information exchange organizations, vendor-based networks, or national networks. Hospitals that indicated that they often sent information electronically using at least one of these methods were coded as ‘often’ sending. Hospitals that indicated sometimes sending information using at least one of these methods (and indicated not using any method often) were coded as ‘sometimes’ sending. Hospitals that did not often or sometimes send by any method were coded as not sending.

For the find domain, hospitals were asked if they search and view patient health information from sources outside their system through electronic methods such as provider portals, interface connections between EHR systems, health information exchange organizations, vendor-based networks, or national networks. Hospitals that indicated that they often searched for information electronically using at least one of these methods were coded as ‘often’ find. Hospitals that indicated sometimes searching for information using at least one of these methods (and indicated not using any method often) were coded as ‘sometimes’ find. Hospitals that did not often or sometimes search by any method were coded as not finding.

For the receive domain, hospital representatives were asked if they receive electronic summary of care records from another care setting outside their hospital system through provider portals, interface connections between EHR systems, login credentials that allow access to an EHR, HISPs that enable messaging via DIRECT protocol, health information exchange organizations, vendor-based networks, or national networks. Hospitals that indicated that they often received information electronically using at least one of these methods were coded as ‘often’ receiving. Hospitals that indicated sometimes receiving information using at least one of these methods (and indicated not using any method often) were coded as ‘sometimes’ receiving. Hospitals that did not often or sometimes receive by any method were coded as not receiving.

For the integrate domain, hospital representatives were asked if they integrated electronic summary of care records received from external providers without the need for manual entry. Hospitals that indicated they integrated electronically received summary of care records routinely were coded as ‘routinely’ integrating, hospitals that indicated that they integrated summary of care records electronically, but not routinely were coded as ‘sometimes’ integrating. Hospitals that indicated that they did not integrate summary of care records electronically were coded as not integrating.

References

- 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and ONC Health IT Certification Program. Final Rule. 2020. Available from: Federal Register :: 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program

- 21st Century Cures Act: Establishment of Disincentives for Health Care Providers That Have Committed Information Blocking. Proposed Rule. 2023. Available from: Federal Register :: 21stCentury Cures Act: Establishment of Disincentives for Health Care Providers That HaveCommitted Information Blocking

- Pylypchuk Y, Barker W, Encinosa W, Searcy T. Impact of the 2015 Health Information Technology Certification Edition on interoperability among hospitals. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2021 Sep 1;28(9):1866-73.

- Health Information Technology Advisory Committee (HITAC). Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2023. 2024. Available from: HITAC_Annual_Report_for_FY23_508.pdf (healthit.gov)

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). 2023. Available from: Trusted ExchangeFramework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) | HealthIT.gov

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. SAMHSA and ONC Launch the Behavioral Health Information Technology Initiative. February 5, 2024. Available from: SAMHSA and ONC Launch the Behavioral Health Information Technology Initiative – Health IT Buzz Health IT Buzz

Acknowledgments

The authors are with the Office of Technology, within the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. This brief was drafted under the direction of Mera Choi, Director of the Technical Strategy and Analysis Division, Vaishali Patel, Deputy Director of the Technical Strategy and Analysis Division, and Wesley Barker, Chief of the Data Analysis Branch.

Suggested Citation

Gabriel MH, Richwine C, Strawley C, Barker W, Everson J. Interoperable Exchange of Patient Health Information Among U.S. Hospitals, 2023. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC. Data Brief: 71. 2024.