An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov

website belongs to an official government organization in the

United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock

(

) or

https://

means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.

Interoperability Among Office-Based Physicians in 2019

No. 59 | July 2022

Increasing interoperable exchange using certified health electronic health records (EHRs), and other information technology (IT) has the potential to improve health outcomes (1), enhance effiency (2) and reduce costs (3). Towards that end, public policy has supported the widespread adoption and use of certified, interoperable electronic health records (EHRs) (4,5). The health IT provisions of the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 (Cures Act) (6) seek to address specific barriers to interoperable exchange of information through (1) health IT certification criteria that enable the use of modern standards to make it easier to share information; (2) provisions that discourage information blocking activities to ensure information sharing is an industry priority; and (3) network governance approaches that ease information sharing across health information exchange networks (6). Using nationally representative survey data, this data brief presents the state of interoperability among office-based physicians as of 2019, providing a baseline prior to compliance deadlines related to these key Cures Act provisions. To establish that baseline, we describe current levels of health information exchange (HIE) among physicians and physicians’ experiences with interoperability, including benefits and barriers. We also examine engagement in various aspects of interoperability and variation in interoperability by physician practice characteristics and the type of data exchanged.

Highlights

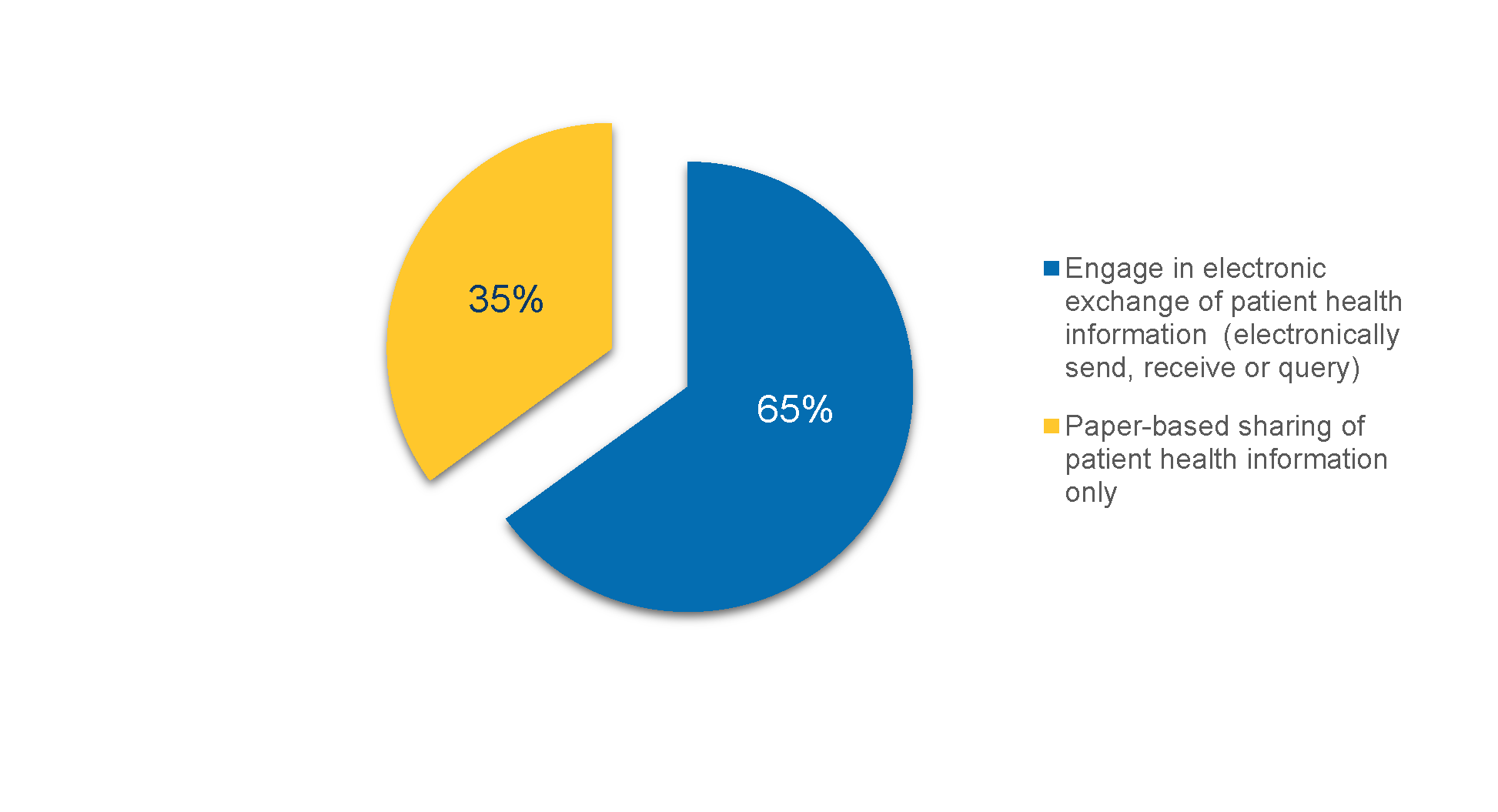

- In 2019, about 65% of physicians engaged in some form of HIE consisting of either finding, sending or receiving information.

- An overwhelming majority (over 75%) of physicians who engaged in HIE experienced improvements in quality of care, practice efficiency, and patient safety as a result of HIE.

- Physicians participating in CMS Promoting Interoperability or Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs were more likely to engage in HIE than non-participants.

- Office-based physicians electronically finding or querying patient information increased by over 40 percent from 2015, reaching 49% in 2019.

65% of physicians engaged in some form of electronic exchange—either sent, received, or queried patient health information—with providers outside of their organization in 2019.

Findings

- About one-third (35%) of physicians used only fax, mail or e-fax to share patient health information with providers outside of their organization.

- About one-third (34%) of physicians engaged in bi-directional electronic exchange sent and either received or queried) patient health information (not shown in the figure below).

Figure 1. Physician’s engagement in sharing of patient health information via electronically sending, receiving, or querying data from external sources in 2019.

Notes: Electronic exchange or HIE refers to electronically sending, receiving or querying of patient health information with providers outside their medical organization

Over 75% of physicians who engaged in some form of HIE reported experiencing benefits related to quality, patient safety and efficiency due to HIE.

Findings

- The most commonly reported benefits experienced by physicians engaging in HIE related to improving care quality (84%) and care coordination (83%).

- Among physicians who engage in HIE, 8 in 10 reported that HIE leads to reduced duplicate test ordering.

- Very few physicians (2 percent) who engage in HIE believed that their practice loses patients to other providers if they exchange their information.

- Among physicians who engage in HIE, 85% reported challenges electronically exchanging information with providers using a different EHR developer.

- At least 70% of physicians who engaged in HIE reported providers in referral networks lacked the capability to exchange.

Table 1. Among physicians engaged in HIE, percent who reported benefits and barriers to HIE, 2019.

| Description | Percent |

|---|---|

| Benefits of Exchange | |

| HIE improves my practice quality | 84% |

| HIE enhances care coordination | 83% |

| HIE reduces duplicate test ordering | 80% |

| HIE prevents medication errors | 79% |

| HIE increases my practice’s efficiency | 76% |

| Barriers to Exchange | |

| Electronic exchange with providers using a different EHR vendor is challenging | 85% |

| Electronic exchange involves using multiple systems or portals | 73% |

| Providers in our referral network lack the capability to electronically exchange | 71% |

| It is difficult to locate the electronic address of providers | 56% |

| Electronic exchange involves incurring additional costs | 55% |

| We have limited or no IT staff | 37% |

| The information that is electronically exchanged is not useful | 20% |

| My practice may lose patients to other providers if we exchange information | 2% |

Source: National Electronic Health Record Survey, 2019.

Physicians participating in CMS Promoting Interoperability or Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs were more likely to engage in HIE than non-participants.

Findings

- Primary care physicians had higher rates of engaging in exchange than medical or surgical specialists.

Table 2. Percent of physicians who electronically exchange by selected characteristics.

| Physicians | Engaged in Exchange (65%) | Did not Engage in Exchange (35%) |

|---|---|---|

| Specialty | ||

| Primary care (ref) | 72% | 28% |

| Surgical | 61%* | 39%* |

| Medical | 55%* | 45%* |

| Participation in Payment Models | ||

| Advanced/Alternative Payment Model | 79%** | 21%** |

| Pay for Performance | 78%** | 22%* |

| Accountable Care Organization | 77%** | 23%* |

| Patient Centered Medical Home | 81%** | 19%* |

| None of above (ref) | 54% | 46%* |

| Certified EHR use | ||

| Yes | 72% | 28% |

| No (ref) | 61% | 39% |

| Don’t know | 50% | 50% |

| Rural | ||

| Yes | 63% | 37% |

| No | 65% | 35% |

| Promoting Interoperability Program or Medicaid EHR Incentive Program Participation | ||

| Yes | 74%* | 26% |

| No | 56% | 44% |

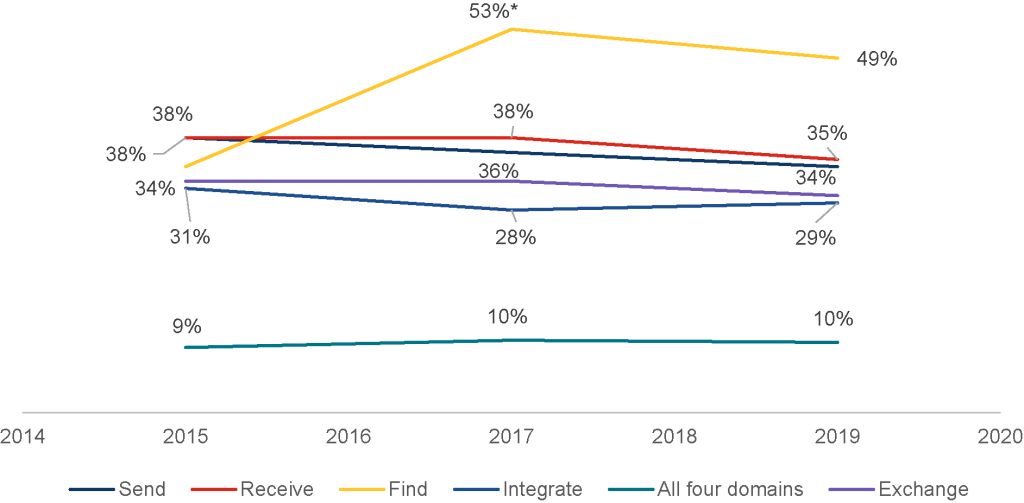

Office-based physicians electronically finding or querying patient information increased by over 40 percent between 2015 and 2019.

Findings

- About half of physicians (49 percent) reported electronically searching or querying for patient health information when seeing a new patient, which is the highest percentage among the four domains of interoperability.

- Across the four domains of interoperability, physician rates of electronically sending patient health information were the second highest (35%).

- Physicians’ engagement in electronically, sending, receiving and integrating information did not change between 2015 and 2019.

Figure 2. Percent of physicians engaging in electronically sending, receiving, searching/querying, and integrating any health information 2015-2019.

Source: National Electronic Health Record Survey, 2015-2019.

*Significantly different from prior year (p<0.05).

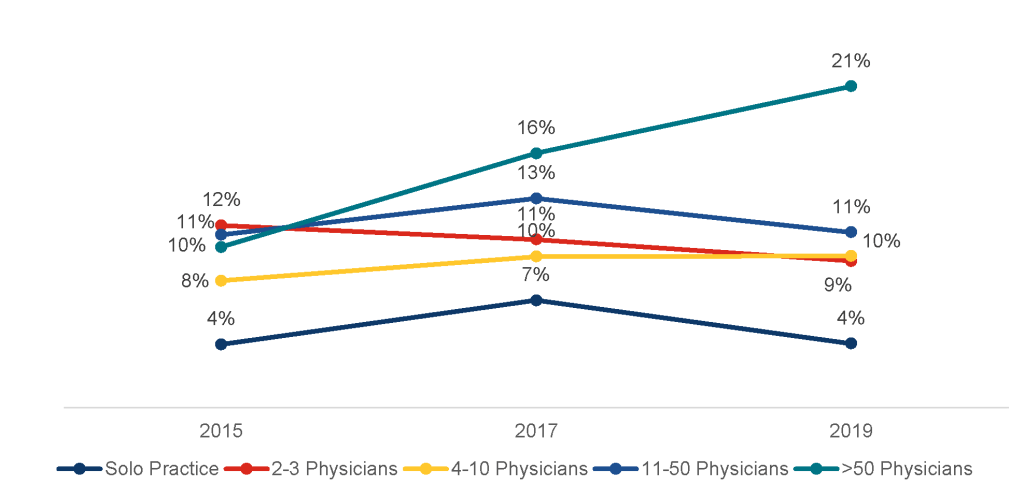

Physicians working in the largest practices (more than 50 physicians) were more than twice as likely to engage in all 4 domains of interoperability in 2019 than in 2015.

Findings

- The percent of physicians engaging in all four domains of interoperability increased among physicians working in the largest practices.

- Among practices with 50 physicians or less, the percentage of physicians engaged in the four domains of interoperability remained mostly unchanged from 2015 to 2019.

- In 2019, physicians in the largest practices (>50 physicians) engaged in all 4 domains of interoperability at almost double the rate of physicians in medium size practices (2-50 physicians) and at 5 times the rate of solo practitioners.

Figure 3. Percent of physicians engaged in four domains of interoperability (send, receive, search/query, and integrate) by practice size during 2015-2019.

Source: National Electronic Health Record Survey, 2015-2019.

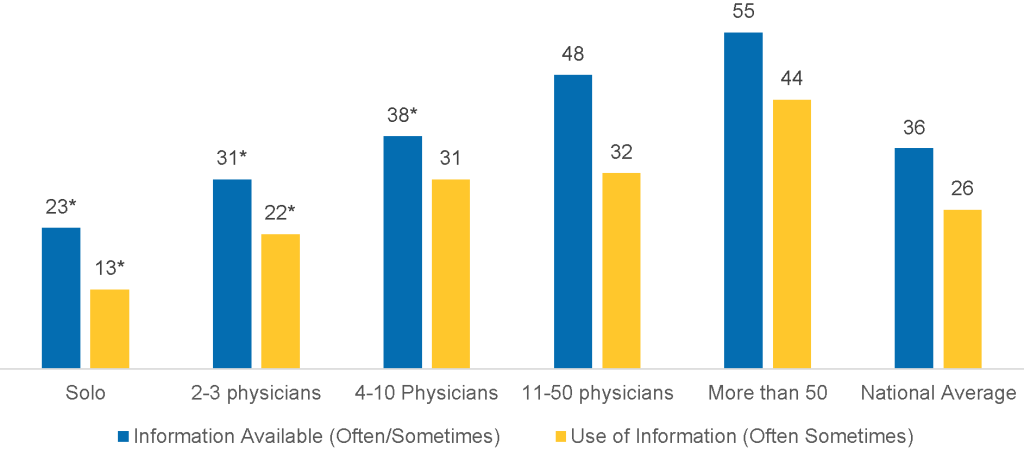

Physicians in larger practices were more likely to have information available from outside sources compared to those in smaller practices.

Findings

- About one-third of physicians (36%) had information available at the point of care and about one-quarter (26%) used information they electronically received from outside sources.

- Physicians in the largest practices (more than 50 physicians) were more than twice as likey to have information available and more than three times as likely to use information from outside sources than physicians in solo practices.

- Among physicians who electronically send, find, receive, and integrate data, 91% have information available at point of care (not showin in figure below).

Figure 4. Percent of physicians that have information electronically available from outside sources and use that information at the point of care by practice size.

*Significantly different from a practice greater than 50 physicians within a relevant category (p<0.05).

More than half of physicians reconciled medications, allergies, and problem lists using data received from another provider in 2019.

Findings

- 43 percent of physicians electronically searched or queried progress/consultation notes.

- Over 36 percent of physicians sent and received consultation notes.

- 28 percent of primary care physicians received an electronic emergency department notification.

Table 3: Percent of office-based physicians that use EPCS technology by physician specialty, 2017-2019.

| Source of Information | Send | Receive | Search/Query | Reconcile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progress/Consultation notes | 36 | 36 | 43 | – |

| Clinical registry data | 16 | 13 | – | – |

| Emergency department notifications | – | 28 | – | – |

| Summary of care records | 27 | 31 | 39 | – |

| Medication list | – | – | – | 68 |

| Medication allergy list | – | – | – | 65 |

| Problem list | – | – | – | 58 |

Source: National Electronic Health Record Survey, 2019.

Conclusions

As of 2019, 65 percent of physicians electronically exchanged patient health information in some manner (either sending, receiving, or querying). More than 75 percent of these physicians experienced improvements in their practice quality, efficiency, patient safety, and care coordination. Many endorsed reductions in duplicate test ordering as a benefit of HIE, which is a well cited benefit that leads to reductions in costs and increased efficiencies. Previous literature has found potential savings from HIE with respect to cost (1), overall hospital efficiency (2), and improvements in patient health outcomes (3).

While engagement in some form of HIE was high in 2019, only 10% of physicians reported engaging in all four measured domains of interoperability (finding, sending, receiving, and integrating information). Looking over time, the percent of physicians electronically finding or querying for patient information increased by over 40 percent between 2015 and 2019. The increase is likely related to specific EHR developers offering capabilities to search for patient health information from within their network of users, as well as increased engagement in national networks that help facilitate query-based exchange. Physicians’ engagement in the remaining dimensions of interoperability (sending, receiving, and integrating information) remained flat.

Our findings highlight barriers to widespread interoperability which may help explain the lack of growth in these other domains of interoperability. First, our findings highlight a divide in interoperability by practice size: physicians in large practices were more likely than other physicians to engage all four interoperability domains in 2019, and the percent of these physicians engaged in all four domains doubled between 2015 and 2019. In contrast, among physicians in practices with fewer than 50 physicians, engagement in interoperability between 2015 and 2019 was flat. Among the 65% of physicians that engaged in any form of health information exchange, the majority reported several barriers to effective exchange with all relevant partners. Physicians reported using multiple systems to enable exchange, difficulties with cross-vendor exchange, and gaps in the use of interoperable technology by other providers in their referral network. These barriers highlight the potentially high cost, complexity and burden involved in widespread information exchange in the current environment.

On one hand, these findings suggest that important progress has been made related to supporting query- based exchange and physicians are experiencing substantial benefit that translates to improved care for patients. On the other hand, more progress is needed to ensure engagement in the remaining interoperability domains to meet needs associated with different use cases, and to ensure effective exchange of a variety of data by physicians in high and low resource settings. That position indicates a strong need for the initiatives that ONC is implementing following the 21st Century Cures Act aimed at simplifying and reducing barriers to widespread exchange (6).

Based on the 21st Century Cures Act (5), ONC issued a rule requiring the adoption of standards-based, HL7® Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR®) application programming interfaces (API) within certified EHRs (7,8). These FHIR-based APIs may provide an opportunity for providers to exchange data in a structured format that allow for more seamless flow and increase integration of data across systems. This may also address barriers related to the difficulty of exchange across different EHR systems. ONC’s work to operationalize the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) may simplify exchange by enabling organizations to connect to multiple networks under one common umbrella regardless of physicians’ current network,and may reduce the need to use multiple systems to exchange information (9,10). TEFCA may also help boost engagement in exchange among those who have not previously participated and thus help address gaps related to physicians’ exchange partners lacking the capability to exchange. Although information blocking among health care providers was not reported as a major issue in this survey, industry-wide compliance with the information blocking provisions from ONC’s Cures Act Final Rule (11), which began April 2021, may further simplify exchange across differing EHR systems and help reduce barriers related to cross-vendor exchange.

In addition to ONC’s efforts, our findings indicate that CMS policies and programs may also improve exchange across a number of areas. For example, although only about one-quarter of primary care physicians electronically received ED notifications in 2019; this will likely increase with the implementation of a CMS policy, effective April 2021, which requires hospitals to send patient event notifications to primary care providers (12). This policy may improve follow-up care on a wide scale (13). Our findings related to higher engagement in exchange among physicians participating in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ CMS’ Promoting Interoperability Component of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and alternative payment models, suggest that those programs may encourage interoperable exchange for those who participate. For example, the high level of physician engagement in reconciliation of medications, allergies, and problem lists using data received from another provider may reflect the role CMS plays in incentivizing this activity as part of the MIPS Promoting Interoperability for practices with over 15 clinicians.

These findings reflect baseline data upon which to assess future progress. The major initiatives described above either have recently begun or will shortly commence: the applicability of the information blocking regulations began in April 2021, TEFCA launched in January 2022, but will be implemented over time, and FHIR API requirements will take effect at the end of 2022. Measuring the impact of these initiatives on physicians’ experiences with interoperability will provide insight on our success in addressing specific barriers, reducing engagement gaps, and ultimately achieving the goal of widespread interoperability.

References

- Walker DM. Hospital efficiency gains from health information exchange participation. Health Care Management Science. 2017DOI: 10.1007/s10729-017-9397-4.

- Brenner SK, Kaushal R, Grinspan Z, et al. Effects of health information technology on patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016; 23:1016-36.

- Richardson, J., E. Abramson, and R. Kaushal. 2012. The value of health information exchange. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, pp. 17-24.

- Title IV of Division B of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), Pub. L. No. 111-5, 123 Stat. 226 (Feb. 17, 2009) (full-text), codified at 42 U.S.C. §§300jj et seq.; §§17901 et seq.

- 21st Century Cures Act. H.R. 34, 114th Congress. 2016. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS- 114hr34enr/pdf/BILLS-114hr34enr.pdf Accessed September 14, 2021.

- Tripathi M. Delivering On The Promise Of Health Information Technology In 2022. Health Affairs Forefront 2022.

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. ONC Cures Act Final Rule. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/05/01/2020-07419/21st-century-cures- actinteroperability-information-blocking-and-the-onc-health-it-certification.

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. FHIR Fact Sheets. “What is HL7 FHIR?” https://beta.healthit.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/What-Is-FHIR-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2021.

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement. https://beta.healthit.gov/policy/tefca. Accessed September 14, 2021.

- Tripathi M Yeager M. 3…2…1…TEFCA is Go for Launch. http://beta.healthit.gov/blog/interoperability/321tefca-is-go-for-launch.

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. Information Blocking. https://beta.healthit.gov/information-blocking. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 42 CFR Parts 406, 407, 422, 423, 431, 438, 457, 482, and 485. “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Interoperability and Patient Access for Medicare Advantage Organization and Medicaid Managed Care Plans, State Medicaid Agencies, CHIP Agencies and CHIP Managed Care Entities, Issuers of Qualified Health Plans on the Federally-Facilitated Exchanges, and Health Care Providers.“ https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-05-01/pdf/2020-05050.pdf

- Dixon BE, Judon KM, Schwartzkopf AL, et al. Impact of event notification services on timely follow-up and rehospitalization among primary care patients at two Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(12):2593-2600.

Definitions

Certified EHR: physicians indicated that their reporting location uses an EHR, and that EHR meets the criteria for Meaningful Use (also called promoting interoperability) as defined by the Department of Health and Human Services.

Find: refers to physicians’ ability to electronically search or query for (or to “find”) patient health information from sources outside of their medical organization.

Integrate: the ability of an EHR system to integrate any type of patient health information received electronically (not eFax) without special effort like manual entry or scanning.

Office-based Physician: physicians that see ambulatory patients in office-based settings, clinics, health centers, or other health system practices.

Public Health Agency: state and local public health agencies support interoperability efforts and data exchange with electronic health records, many of which have been utilized by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Promoting Interoperability Programs.

Receive: refers to physicians’ ability to electronically receive patient health information from other providers outside their medical organization using an EHR system (not eFax) or a Web Portal (separate from EHR).

Send: refers to physicians’ ability to electronically send patient health information to other providers outside their medical organization using an EHR (not eFax) or a Web Portal (separate from EHR).

HIE: refers to physicians’ ability that electronically send or receive patient health information from other providers outside their medical organization using an EHR system or query any patient health information from sources outside of their medical organization.

Data Source and Methods

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics conducts the National Electronic Health Records Survey (NEHRS) survey on an annual basis. Physicians included in this survey provide direct patient care in office-based practices and community health centers; excluded are those who do not provide direct patient care (radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists). The data from this survey came from year 2019.

Among 10,302 total respondents to the survey, 2,280 met the necessary inclusion criteria, of which 1,524 completed all survey items – yielding a response rate of 67% among eligible respondents. Adjustments were made to account for non-response among physicians whose eligibility could not be determined and for those who did not participate in the survey. Responses for the 1,524 records included in the final 2019 NEHRS PUF were weighted to reflect national estimates for approximately 301,603 office-based physicians in the U.S.

Additional survey documentation can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nehrs/documentation/index.html

Suggested Citation

Pylypchuk Y., J. Everson, D. Charles, and V. Patel. (February 2022). Interoperability Among Office-Based Physicians in 2015, 2017, and 2019. ONC Data Brief, no.59. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC.

Appendix Table 1. Percent of physicians who electronically exchange by selected characteristics.

| Physicians | Engaged in Exchange (Overall: 65%) | Did not Engage in Exchange (Overall: 35%) |

|---|---|---|

| Specialty | ||

| Primary care (ref) | 72% | 28% |

| Surgical | 61%* | 39% |

| Medical | 55%* | 45% |

| Ownership | ||

| Physician/Physician group (ref) | 60% | 40% |

| Insurance and other corporations | 67% | 33% |

| Community health centers | 56% | 44% |

| Medical and academic centers | 78%** | 22%* |

| Payment Models | ||

| Advanced/Alternative Payment Model | 79%** | 21% |

| Pay for Performance | 78%** | 22% |

| Accountable Care Organization | 77%** | 23% |

| Patient Centered Medical Home | 81%** | 19% |

| None of above (ref) | 54% | 46% |

| Certified EHR | ||

| Yes | 72% | 28% |

| No (ref) | 61% | 39% |

| Don’t know | 50% | 50% |

| Medicare | ||

| Yes | 66%* | 34% |

| No | 62% | 38% |

| Rural | ||

| Yes | 63% | 37% |

| No | 65% | 35% |

| Medicaid | ||

| Yes | 68%* | 32% |

| No | 49% | 51% |

| CMS Promoting Interoperability Program or Medicaid EHR Incentive Program Participation | ||

| Yes | 74%* | 26% |

| No | 56% | 44% |